- Home

- Jane Yolen

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast Page 7

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast Read online

Page 7

The word die resounded inside her. It was ugly and sharp and it hurt.

She rinsed the pail at the outside tap, then walked back into the house. ‘Done,” she called out to her little brother. “I get dishes tomorrow, and you, Mr. Brat—you get the compost.”

“I hate the compost,” Danny whimpered. “Something’s growing out there.” He spoke in the quiet, whispery, scared voice he had used ever since their father died.

“Of course something’s growing there,” Brancy said. She deliberately made her voice sound spooky.

“It is?” His eyes got wide.

"Volunteers,” Brancy told him. “And if you’re not careful, they’ll get you!”

“Mommmmmmmy,” Danny cried, and ran out of the room.

Moments later he came back, followed by their mother. She was not amused. “Brancy, he has had enough nightmares since ... without you adding to them.” Her mother never actually used the word death. Or cancer. Her conversation was full of odd ellipses and gaps. Brancy hated it. "I need you to be more ... understanding about ... about things.”

“All I said was that volunteers grow up in the compost heap. And you know they do.”

“She said the Bolundeers would get me.” Danny was white faced. “Maybe get all of us. Like they got...” He didn’t say the word Daddy. He didn't have to.

Mrs. Callanish knelt down. “Oh, Danny, a volunteer”—she pronounced the word very carefully—“is a tomato or squash or some other vegetable that grows from the seeds that are thrown into the compost heap. And they can’t possibly get you. Not like ... Have you ever seen a fierce tomato or a mean pumpkin?” She made a face.

“At Halloween,” Brancy said. “All those teeth.”

“Brancy!” Mrs. Callanish’s mouth was drawn down into a thin line.

Brancy knew, even before her mother spoke, that she had gone too far this time. In fact, since her father’s death everything that Brancy said or did seemed wrong, hurtful, awry.

Her mother was changed, too, beyond all recognition. Before, she had been a funny, cozy kind of mom, always ready to listen, even when she was busy. And as a DA, she was always busy. Now she was stem and unreachable. Brancy understood why—or thought she did. Her mother was trying to be brave and strong, like her father had been throughout his illness. But what made everything worse was that her mother never let them talk about him. About his illness, about his death. She just set his memory firmly between the spaces. He was... (gone).... It was almost as though he had never been a part of their lives at all.

“OK, get your homework out of the way and then we can have a chapter of Tolkien tonight. I’ve managed to get most of my work done.” Mrs. Callanish nodded, but there was no warmth in her voice, as if reading to them were a duty she was still willing to perform—but not one she was happy doing.

Brancy knew that Danny would be finished with his homework first. After all, how much homework does a kindergartner have, except maybe coloring? But she had at least an hour of math and social studies and a whole page of spelling words to memorize. Mr. Dooley, her English teacher, was a bear on spelling words. He had won a national spelling bee as a fourth grader and loved to tell them about it. Before her father had died, Brancy had been class champion—and Mr. Dooley’s pet. But she had gotten C’s on her last three spelling tests and had never made up the two she missed because of the funeral. Mr. Dooley didn’t even kid around with her anymore. Which is fine, Brancy thought. Just fine. Mr. Dooley is kind of joofy on the subject of spelling, anyway.

It turned out to be more like three hours of homework, though—one before the Tolkien, and two after—and Brancy was exhausted. Eighth grade was going to be real hard, she decided. The spelling words had been the worst ever: naiad, Gorgon, nemesis, daimonic, centaur, odyssey. They were studying the myths of ancient worlds. Brancy wished the ancient worlds had known how to spell with more regularity. Or had had fewer odd gods and monsters.

“Though how anyone could really believe in this stuff..." she said, slamming the book shut. “It’s all too bizarre.”

“Brancy,” came a whispery voice from the door connecting her bedroom with Danny’s.

She looked up. Danny was standing there, holding on to his bear, Bronco.

“Hey, Mr. Brat, it’s way past ten. What are you doing up?”

“I heard the Bolundeers outside. In the compost.” His chin trembled. “They’re scratching around. And whispering awful things about you and me and Mom. They want to come into the house. Listen.”

She listened. All she could hear were crickets. “You know what Mom said. Volunteers”—she pronounced it again carefully—“are vegetables. And vegetables don’t make any noise. In fact, they are very very quiet.”

“Not these ones,” Danny said. “These are Bolundeers. They want to hurt us. Brancy, I’m scared.”

She started to say something sharp but his face was so pinched and white that she bit back the response. He hardly looked like a kindergartner anymore. In fact, he looked like a little old man. A little old dying man. “Do you want me to snuggle with you till you fall asleep?”

He nodded, clutching Bronco so hard the little bear’s eyes almost popped out.

“OK. I was getting tired of Gorgons and centaurs, anyway.”

“What are those?”

“Far worse than talking veggies, trust me.” She followed him back to his bed. Tacking in next to him, she said, “Why don’t I sing you something?” He nodded, and so she started with their father’s favorite lullaby, the one he always sang when they were sick and couldn’t fall asleep: “Dance to Your Daddy.” Only, unlike their father, she sang it on key.

Danny dozed off at once, but Brancy could not sleep. The song only served to remind her that her father was no longer around. He had suffered horribly before finally dying, and God had been no help to him at all. Even though they had all prayed and his partner had had a mass said for him. It didn’t matter that her father had been strong and brave before he had gotten cancer. With medals from the city after having been injured in the line of duty. He hadn’t died when some man crazy with drugs had tried to kill him with a knife. Or later, when he had shielded two hostages with his own body while a would-be burglar had shot at them. It was stupid lung cancer from his stupid smoking that had killed him. She tried to remember what her father had looked like, either before the cancer or after. But all that came to mind was what they had left of him, in a jar on a shelf in her mother’s den.

Ashes.

Morning was dirty and gray as an erased blackboard. Brancy got up from her brother’s bed, where she had slept fitfully, on top of the covers. She brushed her teeth quickly, ran her fingers through her short hair, and got dressed with a lack of enthusiasm. The other girls in her class, she knew, made dressing the long, important focus of their day. But ever since ... She stopped herself. Then, afraid that she was beginning to sound like her mother, she said aloud, “Ever since Daddy died..." Well, clothes and things weren’t so important anymore. Or school.

In fact, Brancy was so tired, she dozed through most of her classes. She was all but sleepwalking when she picked up Danny from afternoon kindergarten. Still, she was awake enough to see that his pinched-old-man look was gone, and she smiled at him. Hand-in-hand they walked back toward home, with Danny babbling on and on about stuff in a normal tone. Only, when they turned the corner of Prospect Street, he was suddenly silent and his face was the gray-white of old snow.

“Cat got your tongue, Mr. Brat?” Brancy asked.

“Do you think..." he whispered, “that the Bolundeers will be waiting for us?”

“Oh, Danny!” Brancy answered, unable to keep the exasperation in her voice hidden. She was too tired for that. “Mom explained. I explained.” She shook her head at him. But his hand in hers was damp.

“Don’t let them get me, Brancy,” he said. “Don’t let them hurt me. I’m not brave like Daddy.”

She dropped his hand and knelt down in front of him so they were eye-

to-eye. “No one,” she said forcefully, “is going to hurt you. Not while I’m around.”

“Daddy got hurt.” His eyes teared up.

She dropped her books to the ground and put her arms around him. She couldn’t think of anything to say. And besides, their mother didn’t want them to talk about it. She found herself snuffling, and Danny pulled away.

“Don’t cry, Brancy,” he said.

“I’m not crying. I’ve got a rain cloud in my eyes.” It was something their father used to say.

“Oh, Brancy!” Danny was suddenly bright again, as if he had forgotten all about his fears. He took her hand. “I think we need to go home now.”

And they did. Straight home. Without talking.

Brancy did her homework in the living room, to keep an eye on Danny while he watched television. But she was so engrossed in the reading she didn’t notice when he left the room in between commercials. When she realized he was gone, she got up, stretched, and went to look for him.

He wasn’t downstairs, and she raced up the stairs to see if he was—for some reason—in the bedrooms. Sometimes, she knew, a five-year-old could get into a lot of trouble by himself. But he wasn’t upstairs, either. She was dose to panic when she glanced out the bedroom window and saw him by the compost heap. What he was doing there was so shocking, she screamed. Then she ran down the stairs and outside, without taking time to put her shoes on. The grass soaked her socks.

“Danny!” she cried. “Stop! Oh, Danny. What have you done?”

He turned to her, smiling. “Daddy will take care of those Bolundeers all right. Just like he takes care of all the bad guys.”

She took the urn from him and looked in. It was totally empty. She didn’t dare stare over his shoulder into the compost heap, where she knew the gray ashes would already be settling into the slime. “Oh, Danny,” she whispered, “we can’t tell Mommy. We just can't.

And they didn’t. Not at dinner, and not at bedtime. Danny because he’d promised Brancy, and he did not know exactly what was wrong. And Brancy because she did know. Exactly.

That night, as she lay in her bed, Brancy heard the sound Danny must have been listening to the night before. The crickets, of course. But underneath their insistent high-pitched chirrupings, something else. Something odd and ugly, scratching and scrabbling across the grass. It sounded awkward and eager, as if it had gained strength before judgment, as if it were hungry, as if it were heading toward the house.

Brancy got up and looked out of the window, but she couldn’t see anything out there. Except a series of strange flat black shapes that seemed to hunch and bunch through the grass. But the moon was full and the lawn was covered with shadows. Surely that was what she was seeing.

She shut her window as quietly as possible and pulled down the shade. Then she crept into Danny’s room, her heart thudding so loudly she thought it would wake her mother down the hall.

Danny was clutching his bear as if he were frightened, but he was fast asleep. Brancy lay down next to him, afraid to think, afraid to move again, afraid to breathe.

The strange scratching, scrabbling sound seemed to come closer, reaching below Danny's window. Brancy forced herself to get up, to go over to the window and shut it. It slammed down on the sill with a loud whack as sharp as gunshot. But not before Brancy saw the shadows rising up, like some sort of anonymous and deadly gang, their shadowy fingers pointing at her, their shadowy mouths calling in voices as soft and persuasive as dreams. "Danny ... we’re coming for you next!”

“No!” she cried out loud, “not Danny.” She flung herself back onto the bed, setting herself over Danny to protect him. She could feel him breathing beneath her, gentle and trusting; her own breathing was a harsh rasp.

And then she heard something else. It was faint, so faint that at first she thought she was only wishing it. But it got louder, as if whatever made that particular noise had come closer, or had gained its own particular strength from her. It was—she thought—a sound that was strangely off-key. But she recognized it. It was a song, and she sang along with it, quietly at the beginning, then with growing gusto: “Dance to your daddy, my little laddy...”

Danny stirred in his sleep and nuzzled the bear.

“Brancy?” Her mother’s voice floated down the hall.

Brancy stopped singing just long enough to call back: “Under control, Mom.”

The song seemed to catch up with the eager scratching, then overtake it. There was a moment of strange cacophony, like some kind of grunge band suddenly playing beneath their window.

And then, as if it had been a vine cut down, the scratching stopped.

Slowly the off-key song faded away, and all she could hear then were the ever-present crickets and the faraway hooting of a screech owl, like a lost child crying in the distance.

Brancy got up, went to the window, and slowly raised it. The air was soft and a shred of cloud covered the full moon. She thought it might soon rain.

"I love you, Daddy,” Brancy whispered to the lawn and, beyond it, the compost heap. Then she closed her eyes, which had rain-clouded over with tears. "I miss you.” She went back to her own bedroom and lay down on the bed. A minute later she felt someone lift the covers up and over her and hum a bit of an off-key tune.

She didn’t open her eyes to see who it was.

She didn’t have to.

The next morning at breakfast, Mrs. Callanish stood by the table looking stem, the urn in her arms.

Brancy started to say something, but her mother shook her head.

“I had the most amazing dream last night,” she said. “About your ... father.” She took a deep breath. "I’ve been wrong to keep his ashes hidden in my den. To make a shrine of them. To forbid you to talk about him and how hie died.”

Brancy took a deep breath, this time determined to confess what had happened.

But her mother continued talking. “Let’s go and spread the ashes in the garden. It was his favorite place. He’ll like being there.”

“But..."Brancy began, then she looked over at Danny. He was smiling. It was a secret, knowing kind of smile.

Suddenly she understood. The ashes—which she had seen him shake out onto the compost heap—were somehow back in the urn. And then she remembered the soft touch of the shadowy hand on her covers, the soft off-key humming above her bed.

“We can sing Daddy’s song while we do it,” Danny said. “About dancing.”

“I didn’t know you knew it,” Mrs. Callanish said.

“I know it all,” Danny said.

“And what you forget,” Brancy added, “I’ll remember.”

The Bridge's Complaint

Trit-trot, trit-trot, trit-trot, all day long. You’d think their demned hooves were made of iron. It fair gives me a headache, it does. Back and forth, back and forth. As if the grass were actually greener on one side one day, on the other the next. Goats really are a monstrous race.

It makes me long for the days of Troll.

We never were on more than a generic-name basis. He was Troll. I was Bridge. It takes trolls—and bridges, for that matter—a long time to warm up to full introductions. So I never had a chance to know his first name before he was ... well ... gone. But he was a pleasant sort, for a troll. Knew a lot of stories. Troll stories, of course, are full of blood and food, food and blood. But they were good stories, for 11 that. Told loudly and with great passion. I really do miss them.

Not that I don’t have a few good stories of my own to tell. I mean, I wasn’t always a Goat Bridge. Long before that demned tribe arrived to foul my planking, I was a Bridge of Some Consequence. Mme. d’Aulnoy herself traversed my boards. And her friend Mme. le Prince du Beaumont. Ah—the sound of wheels rolling. There is a memory to treasure.

None of this trit-trot, trit-trot business.

But then the dear ladies were gone and the meadows, once pied with colorful flowers, were sold to a goat merchant, M. de Gruff. He pastured his demned beasties on both sides of my riv

er. They sharpened their horns on my railings, pawed deep into the earthen slopes, and ate up every last one of the flowers. The grass in the meadows was gnawed down to nubbins by those voracious creatures. In other words, they made a desert out of an Eden.

Trit-trot, trit-trot, indeed.

So you can imagine how thrilled I was when Troll showed up, pushing his way upstream from the confluence of the great rivers below.

He wasn’t much to look at when he arrived, being young and quite thin. Of course he had the big bran-muffin eyes and the sled-jump nose and the gingko-leaf ears that identify a troll immediately. And when he smiled, there were those moss green teeth, filed to points. But otherwise he was a quite unprepossessing troll.

Trolls are territorial, you know, and when food gets scarce, the young are pushed out by the older, bigger, meaner trolls. Or so my Troll told me, and I have no reason to disbelieve him. He said, "Me dad gave a shove when he got hungry. I had to go. Been on the move awhile.”

That was an understatement. Actually he had been wading through miles of river before he found me unoccupied. He must have thought it paradise when he saw all those goats.

Not that he could have run across the fields after them. It is a well-kept secret that trolls must have one foot in the water at all times. Troll told me this one night when we were trading tales. They call it waterlogging. Troll even sang me a song about it that went something like this:

Two feet wet,

None on shore,

You will live

Evermore.

One foot wet,

One foot dry,

You will never

Need to cry.

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

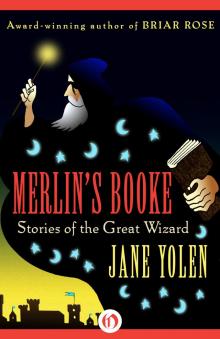

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

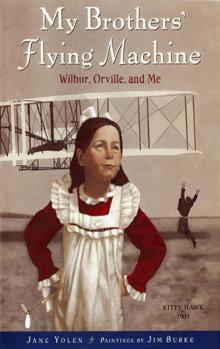

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

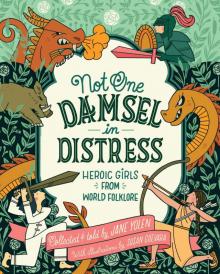

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

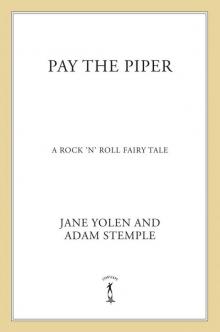

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool