- Home

- Jane Yolen

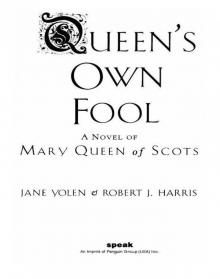

Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Copyright Page

FRANCE - 1559-1560

Chapter 1 - RHEIMS

Chapter 2 - IN THE PALACE

Chapter 3 - GREAT HALL

Chapter 4 - PERFORMANCE

Chapter 5 - THE GARDEN

Chapter 6 - FAREWELLS

Chapter 7 - THE BATH

Chapter 8 - MASS

Chapter 9 - WIT

Chapter 10 - LESSONS

Chapter 11 - MORE LESSONS

Chapter 12 - THE CHESS GAME

Chapter 13 - THE GARDEN AT AMBOISE

Chapter 14 - LA RENAUDIE

Chapter 15 - DEATH OF A KING

Chapter 16 - DECISIONS

Chapter 17 - ACROSS THE WATER

SCOTLAND - 1560-1567

Chapter 18 - LANDING AT LEITH

Chapter 19 - MASS AND MOB

Chapter 20 - THE BLACK CROW

Chapter 21 - ANGELS AND IMPS

Chapter 22 - A FRIEND AT LAST

Chapter 23 - THE MARRIAGE RACE

Chapter 24 - PRINCE CHARMING

Chapter 25 - A HUSBAND FOR THE QUEEN

Chapter 26 - DISASTER

Chapter 27 - WEDDING MEATS

Chapter 28 - SPILLING GOOD WINE

Chapter 29 - MURDER

Chapter 30 - GAMBIT

Chapter 31 - ESCAPE

SCOTLAND - 1567-1568

Chapter 32 - APPARITION

Chapter 33 - A WEE LAD

Chapter 34 - ILLNESS

Chapter 35 - KIRK O’FIELD

Chapter 36 - DEATH IN THE NIGHT

Chapter 37 - REFUGE

Chapter 38 - SAFETY

Chapter 39 - TRIAL AT THE TOLBOOTH

Chapter 40 - CASTLE SETON

Chapter 41 - PLANS

Chapter 42 - MOUSE AND LION

Chapter 43 - ISLAND PRISON

Chapter 44 - WINTER PRISON

Chapter 45 - A MINUTE FROM FREEDOM

Chapter 46 - ANOTHER PLAN

Chapter 47 - MAY DAY FEAST

Chapter 48 - OVER THE GREY WATER

Chapter 49 - PARTINGS

EPILOGUE

“ONLY THE QUEEN MATTERS,” PIERRE SAID.

Just then the servants began to clear away the remains of the banquet with a minimum of noise. The feasters ate silently as well. One would think that such a feast would be abuzz with conversation and laughter, but everything was oddly quiet, as if no one were allowed to speak above a whisper.

This was not a happy party.

Then the queen looked up and, seeing us, nodded her head.

At us.

At me.

Only the queen matters. I heard Pierre’s voice in my head.

“Your Majesties, honored lords and ladies of France,” Uncle declared, “we present to you the renowned skills of Troupe Brufort, as witnessed in the courts of Italy, Burgundy, and Spain.”

I did not show on my face what was in my mind. I did what Uncle wanted.

I smiled.

He waved us forward and our first—and only—perfor—mance before the King and Queen of France began.

OTHER SPEAK BOOKS

To David and Debby,

who loved this book first

J.Y. and R.J.H.

Speak

Published by Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.,

345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

First published in the United States of America by Philomel Books,

a division of Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers, 2000

Published by Puffin Books, a division of Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers, 2001

This edition published by Speak, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 2003

9 10

Copyright © Jane Yolen and Robert J. Harris, 2000 All rights reserved

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PHILOMEL EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Yolen, Jane.

Queen’s own fool: a novel of Mary Queen of Scots / by Jane Yolen and Robert J. Harris

p. cm.

Summary: When twelve-year-old Nicola leaves Troupe Brufort and serves as the fool for Mary,

Queen of Scots, she experiences the political and religious upheavals in both France and Scotland.

1. Mary, Queen of Scots, 1542—1567—Juvenile fiction. 2. Scotland—History—Mary Stuart,

1542-1567—Juvenile Fiction. [1. Mary, Queen of Scots, 1542-1567—Fiction.

2. Scotland—History—Mary Stuart, 1542-1567—Fiction. 3. Fools and jesters—Fiction.

4. Kings, queens, rulers, etc.—Fiction.] I. Harris, Robert J., 1955—II. Title.

PZ7.Y78Qu2000 [Fic]—dc2t 99-055070

eISBN : 978-1-101-07774-0

www.janeyolen.com

http://us.penguingroup.com

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHORS

Mary Queen of Scots is an historical figure. So is La Jardinière, one of her three female jesters.

We know much about the queen, though opinions about her vary widely. Her uncle, the opulent Cardinal of Lorraine, wrote that when she was still a child: “King (Henry II) has taken such a liking for her that he spends much of his time in chatting with her ... and she knows so well how to entertain him with pleasant and suitable subjects of conversation as if she were a woman of four and twenty.” But the wintry-souled preacher John Knox called her a “honeypot” and wanted to burn her as a sorceress.

At age ten Queen Mary was already writing to her mother about Scottish politics. At thirteen she composed and presented a speech in Latin to the French court. We know how she looked, what clothes she wore, what songs she admired, what friendships she had with her personal servants, and how—in the words of one critic—she was “Fond, foolish, pleasure-loving ...” How could she not be? She had been brought up in the court of France, known as the most elegant, most joyous, and most lax in Europe. Of course she would share that court’s virtues as well as its considerable vices.

We know only this much about Mary’s French fool La Jardinière, all from the court records: that she was female, that she was given several expensive dresses, that she was given linen handkerchiefs, and that she was sent home to France with a large payment when the queen went off to England.

Where history ends, storytelling begins.

FRANCE

1559-1560

Did Destiny’s hard hand before,

Of miseries such a store,

Of such a train of sorrows shed

Upon a happy woman’s head?

from a poem by

MARY QUEEN OF FRANCE, 1560

1

RHEIMS

The rain poured down throughout the day, hard and grey as cathedral stone. One by one, we dragged to a halt. I stopped dancing first, then Annette, our skirts hanging in damp folds, tangling in our legs.

“It is like walking with dead fish,” I said. “Slip-slap.”

Annette giggled. But then she found everything amusing. Even in the rain.

Taking the tin whistle from his lips, Bertrand flicked it several times, trying to rid it of water. Nadine’s tambourine went still, and she shifted little Jean to her other hip.

Now Pierre alone kept going, flinging the clubs into the air. One and two, three and four, five ... I wondered if he were going to try seven at once, here on the drowned streets of Rheims where no one would see him fail.

/> “What are you doing?” Uncle Armand cried out, and began hitting the rest of us for stopping. “Troupe Brufort does not stop for mere rain!” His hand was like some small, fierce, whey-colored animal nipping and pinching where it could.

Pierre dropped one of his rain-slicked clubs. It landed with a loud splash in a puddle at his feet. He stooped to pick it up.

Uncle Armand turned and slammed Pierre on the head with the gold-topped cane. “Clumsy fool! Did I tell you to stop?”

Stepping to Pierre’s side, I began, “But Uncle, there is no one on the street. Even the beggars have left the road to seek shelter. We have come to the holy city for nothing, and ...”

Whap! This time the cane fell on my head, and I saw stars. Pierre had been smarter, going right back to his juggling. Would I never learn? One day Uncle would kill me with his cane.

“Mademoiselle La Bouche du Sud,” Uncle said, meaning Miss Mouth from the South, “says we have come to Rheims for nothing. But she is the nothing, not we.”

This time I bit my lip to keep from answering back. One day, I swore, I would break Uncle’s cane over my knee.

Uncle was not finished speaking, though. His nose wrinkled as if he had smelled something foul. “We have come to Rheims for the young king’s crowning. Fortunes will be made here. The new queen loves pageantry, songs, dances, mummery. All of which Troupe Brufort can supply.”

“But Uncle ...” I began, wanting to remind him that the city was draped in black for the old king’s death—“A lance in his eye while jousting,” a walleyed beggar girl had said. “The new king insists on a long mourning.” So none of the grand folk racing to the coronation had heart or coins for street players.

“Dance!” Uncle commanded. “Now! Good will come of it.”

“Wet will come of it,” I mumbled. But not so he could hear.

Bertrand began to play a three-step on the pipe, and Nadine beat the tambourine against her sodden skirt once more. Annette and I shuffled our feet obediently in time and Pierre tossed up three clubs in a rotation he could do even in a pouring rain.

“Bon!” sang out Uncle, a rare compliment.

Just then a well-dressed merchant and his three dark-clad daughters hurried past us, holding cloaks over their heads. The girls squealed in their distress.

“Papa! My boots!” cried both the eldest and the youngest.

“The rain is ruining my skirts,” the middle one added.

“Talk less,” their papa responded. “Run faster.”

Uncle insinuated himself into their way, smiling. He is like a serpent when he smiles—all lips, no teeth. “Pause for a moment, good sir. Witness the wondrous skills of Troupe Brufort, only recently returned from the courts of Padua, Venice, Rome.”

Of course, Troupe Brufort had never been to any of those places. Only I, born in my papa’s beloved Italy, had traveled beyond France. But Uncle always dropped great names like a horse with too much grass in its mouth letting fall the extra bits.

The merchant spun around Uncle and hastened his whining daughters homeward, the backs of the girls’ tufted dresses looking like a dark rolling ocean.

“This is stupid, Papa,” Pierre muttered, wiping his clubs one at a time on his shirt, a useless action, as his shirt was as wet as the clubs. “We will all come down with a fever, and for nothing.”

Ignoring Pierre, Uncle strode over to Bertrand and snatched the pipe from his mouth. “Enough tiddly-piddly, boy! Do your tumbling. Nadine, strike up a beat.”

Annette and I clapped in time to the tambourine, making soft smacking noises. One and two and one-two. On Nadine’s hip, little Jean awoke and tried to catch the raindrops.

All at once, a clatter of hooves on the cobbles to our left, and a dark carriage approached, drawn by two dappled horses, their backs so wet, the hair looked black. On the carriage door was a coat of arms and a motto, but as I could not read, I did not know what it said. I glimpsed a red uniform under the driver’s cloak, the only bit of color I had seen in the city so far. Then the driver drew the cloak more firmly around his shoulders and that brief flame was quenched.

Beside the driver was another man, shaking as with an ague.

Uncle nodded. “Ha!” he cried, as if the appearance of the carriage vindicated all the beatings.

The carriage pulled up close to us, so close that Bertrand hesitated in his tumbling for fear of frightening the horses. A gentleman with a thin mustache peeked out of the window.

“Do not stop!” hissed Uncle.

Bertrand leaped up again, doing first a double twist, then a series of no-handed cartwheels.

Annette and I added some shuffling steps to our hand claps, and Pierre lofted five clubs.

“Climb,” I whispered to Annette.

“But my skirts ...” she began.

“To the devil with your skirts,” I said, locking my fingers together and holding my hands down low.

Annette was so shocked at my swearing, she climbed without further comment, scrambling to my shoulders and leaving muddy footprints on my bodice. I gripped her ankles. Luckily she was only six years old and very light.

“Smile,” Uncle hissed.

We smiled.

The shaking man climbed down from his station on the carriage and stood at attention by the carriage door. He had a disgruntled air, as if he dearly wanted to be in a warm, dry spot.

The gentleman in the carriage just sat there, rubbing his mustache, while his servants got soaked, and all for the sake of our poor show. If he were to throw us a good-sized purse, Uncle might let us stop and find someplace dry. I smiled again, what Pierre calls my “winning smile” and Uncle calls “Nicola’s grimace.”

“Enough!” the gentleman announced abruptly. “You will do.”

Gratefully I lowered Annette to the ground. Her little golden curls were now hanging in long, wet strands. Pierre tucked the clubs under his arms and Bertrand—at the long end of a tumbling run—came back unhurriedly.

“Do?” Uncle brightened.

The gentleman pursed his lips. “As I have seen no other troupe on this forsaken street, you will have to do. Jacques, show them the way to the palais. Then he banged his cane against the carriage roof and called, ”Get me home before I catch my death.”

The servant Jacques jumped aside in time to avoid a splash of water from the carriage’s wheels as it pulled away, though Bertrand had no such luck and was drenched to the knee.

As soon as his master was gone, Jacques let his shoulders droop. Glancing sourly at us, he rubbed his nose with the flat of his hand. “Follow me, and try to keep up. I do not want to dawdle in this weather.”

“Whom have I the extreme honor and privilege to be addressing, monsieur?” Uncle asked in the oily voice he used when speaking to rich people.

“It is no honor addressing me,” Jacques answered, turning away and saying over his shoulder, “nor privilege neither. You had best save your fine manners for the new king.”

For a moment Uncle froze, his lips silently forming the word “king.”

The king. I thought. With the pretty queen who loves pageants.

Then Uncle stirred, bowed and waved at us, his face suddenly exultant, open like a dried flower bed after a good shower. “Come along. Do not just stand there. The king is waiting for us. And,” he added, “remember—obey my every word if you wish to make a good impression. Nicola, you especially, do not open your mouth.”

Pierre and I hurried to the wooden cart, each taking hold of a handle. The ancient cart creaked and protested, but for the first time ever it sounded like music to me.

Bertrand, Annette, and Nadine grabbed their sacks off the ground, slinging them into the cart, then followed behind us. For once there was no chatter. We were going to entertain in a palace. How could anyone complain—even of the rain?

Perhaps we had come to Rheims for something after all!

2

IN THE PALACE

Marching ahead of the cart, a step behind Jacques, Uncle wen

t proudly. His balding head was tilted at such an angle, he looked as though he were leading a parade rather than following a sullen servant along a rain-soaked backstreet.

Jacques looked as if he had a bean stuck up his nose. He never even glanced around to see if we followed. Clearly he wanted no one in Rheims to think he had anything to do with our ragtag troupe.

The rain began to ease at last, but the evening was drawing in. Rheims was still grey above, grey below, and grey in the middle, but there was a small, hopeful, golden glow in my belly. Each step I thought: But one more step and one more and one more towards the warmth.

I was so concentrated on getting to where we were going, I had no idea where we were, and so I was entirely startled when Nadine cried out, “Look, children, there is the king’s palace.”

Jacques sniffed at her. “No, madam, that is the palace of Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine and Archbishop of Rheims. The king and queen are but guests here. But it is our destination.”

The cardinal’s palace was certainly large, but not nearly as large as some we had seen in our travels. As for that stone wall—we were connoisseurs of walls: cathedral walls, palace walls, the walls of fortresses and castles. They were often the backdrops for our performances, though we had never actually been invited inside before.

Still—walls meant roofs. Roofs meant shelter. Suddenly I was filled with new energy. Grabbing my cart handle, I gave it a hard shove which skewed the cart so that it wobbled on the cobbles.

“Easy,” hissed Pierre. “Do not overturn the cart. Not now.”

“As if I could!” I countered.

“Amazon!” he said.

“Flea!”

“Fleabite!”

And then we looked at one another and laughed. We were as close as brother and sister. Closer, really, for although we were not the same age, we were of the same disposition. We had chosen one another as confidante and friend.

“Be quiet, all of you,” Uncle said, “and Nicola especially.” He raised his cane as a warning, for Jacques was talking to two guards at a small portal.

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool