- Home

- Jane Yolen

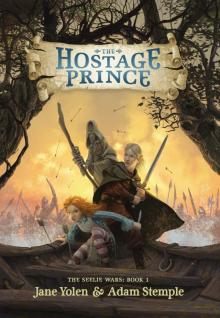

The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Read online

Books by

JANE YOLEN

Young Merlin Trilogy

Passager

Hobb

Merlin

Sword of the Rightful King

The Last Dragon

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

Snow in Summer

The Pit Dragon Chronicles

Dragon’s Blood

Heart’s Blood

A Sending of Dragons

Dragon’s Heart

Dragon’s Boy

Sister Light, Sister Dark

White Jenna

The One-Armed Queen

Wild Hunt

Wizard’s Hall

Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Books by

ADAM STEMPLE

Singer of Souls

Steward of Song

Books by

JANE YOLEN and ADAM STEMPLE

Pay the Piper: A Rock ’n’ Roll Fairy Tale

Troll Bridge: A Rock ’n’ Roll Fairy Tale

B.U.G. (Big Ugly Guy)

The Hostage Prince: The Seelie Wars—Book I

THE SEELIE WARS: BOOK I

Jane Yolen & Adam Stemple

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Young Readers Group

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

USA / Canada / UK / Ireland / Australia / New Zealand /

India / South Africa / China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit www.penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Viking,

an imprint of Penguin Young Readers Group, 2013

Copyright © Jane Yolen and Adam Stemple, 2013

Original map conceived by John Sjogren, rendered by Eileen Savage

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE

ISBN 978-1-101-60243-0

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Terri Windling, Ellen Kushner, and Delia Sherman, that magical trio, and Sharyn November, who asked for it—J.Y.

For my favorite changeling, Alison—A.S.

CONTENTS

Also by Jane Yolen

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map of the Shifting Lands

1. Snail Wakes

2. Aspen Enters the Hall

3. Snail in the Kitchen

4. Prince Aspen Regrets

5. Snail in the Tower Room

6. Aspen’s Desperate Plan

7. Snail Spies the Queen’s Hallway

8. Aspen’s Packed Bag

9. Snail Underground

10. Aspen Follows the Wall

11. Snail in the Dungeon

12. Aspen Falls

13. Snail Speaks to the Ogre

14. Aspen Spies Skellies and Cells

15. Snail’s Fight

16. Aspen At the Tower

17. Snail Ties a Knot

18. Aspen in Rough Waters

19. Snail and the Mer

20. Aspen Leads On Shore

21. Snail on the Path

22. Aspen in the Cook’s Cave

23. Snail’s First Birthing

24. What Aspen Brings to the Battle

25. Snail Finds the Way

26. Aspen in the Castle

27. Snail’s Time Out

28. Aspen Leads the Way

About the Authors

SNAIL WAKES

“Shift yourself, Snail. It’s half morning and the queen’s baby will be born this day.” The midwife gave her apprentice a sharp slap on the rump with the measuring stick, hard enough to sting through the covers. Then she waddled back into the parlor room they shared with the other midwives.

“Mmmmmmf,” Snail replied. There’d been a celebration last night with the backstairs folk—the cook boys and ostlers, the dog boys and castle maids—all of them wild with anticipation. Since the queen gave birth only once every hundred years, none of them had ever seen a baby royal. They’d stayed up much too late eating enough cake to feed the entire Unseelie army.

“But why?” Snail had asked the midwife in the first days of her actual apprenticeship. She’d been four at the time, and trying to tie her shoes.

Hands on ample hips, Mistress Softhands replied, “Since the queen lives so long, the palace would be crammed full of royal babes all fighting for a chance at the throne if she had them once a year like ordinary Unseelie folk. And we can’t have that.”

“But why?” Snail had repeated. Sometimes she was slow at grasping such things. Slow at spells, too. Like the lace tying. She knew she should have mastered that spell by three years old. All the other new apprentices had. And there she was still struggling with it a year past. Usually the laces she’d just bespelled would simply sigh open. Or she’d trip over them minutes after she’d just bound them up. Then Mistress Softhands would scold her. Gently, but firmly. Hold her hands over the laces just so. Correct her spelling.

“But why?”

“Think, Snail, think. It would make all our lives miserable, that would, with dozens of young royals crowding the palace. Spats, quarrels, spells thrown hithery-thithery, duels, wars.”

It makes sense, in a way, Snail had thought at the time, though later, when she was old enough to know a thing or three about the court, she’d thought differently. There were already spats, quarrels, tongue-lashings, and duels between the royals. And when spells were hurled about carelessly, well, it was the underlings, apprentices, and other non-toffs who bore the brunt of them.

Wars, though . . . those are few and far between. Too dangerous. And, for the long-lived fey, too final. But at least, Snail thought, I’m smart enough not to say so aloud.

All throughout the royal palace there were spies, turncoats, tittle-tattlers, lickspittles, liars, moles, patrols, lackeys, flunkies, toadies, snoops, spooks, and just plain liars-for-a-penny. An apprentice—even a midwife’s apprentice—could just . . . just disappear after having voiced such thoughts to the wrong fey. And no one actually knew who the wrong fey might be until it was too late.

Best to be leery and wary, than teary and buried, was the apprentice creed.

“Snail!” Mistress Softhands’ voice split the fusty air.

Snail tore off her bedsocks and pulled on fresh underclothes and, after them, her striped leggings. Then she bent over to put on her shoes, good sturdy cowhide shoes with fat, tough laces. Apprentice shoes, not the soft, fawn-skin dancing slippers that the court ladies favored, of course. Or even the calf-leather sandals of the ladies-in-waiting. The stone floors of the palace were far too cold to go around even for a few minutes without some kind of foot cover—unless of course one was a satyr with hooves, or a hall hound with furred feet, or a drow with those clacketing, scaly claws. Any skin-footed fey knew that without shoes on one’s feet would turn into ice for the rest of the morning.

Snail held her hands over the laces just so. Said the spell.

/>

Tie and bind

Lace to leather,

Keep these pieces

All together.

Ally-bally bargo.

It was a children’s spell, of course, but at least one she could count on for as long as needed. And she’d never say it in front of another fey or they’d tease her till she wept. Feys were not supposed to weep unless it was for the death of a queen. Or king.

As she worked the spell, Snail thought to herself, But really, the queen gives birth only once in a hundred years? It still made little sense. Snail herself had grown up without any brothers or sisters, and she thought it hard that a royal baby should have to live so lonely a life. Of course a royal baby would have nurses and maids and ladies- or gentlemen-in-waiting, would have cooks, nannies, tutors, and . . .

“And me,” she whispered, though she knew that even should she be called upon to help Mistress Softhands with the birth, she’d never be allowed to actually hold the royal baby.

Or even, she supposed, see it again except from very far away. A midwife’s apprentice was hardly a suitable companion for a prince. Or a princess, if the luck ran that way.

Of course the queen of Faerie, Snail thought, hardly needs a midwife. Her babies slip out with a bit of magic and a good dose of warm oil. Or so any outsider might think.

But royal or not, there were still dangers. No one in the Unseelie Court was likely to forget the baby prince named Disaster of two hundred years past who’d been hanged in his own cord before a spell could get him out. Since that time, royal births were always attended not only by one or two midwives, but by all of the birthgravers in the kingdom, along with their apprentices. What Mistress Softhands called “pulling up the drawbridge after the moat dragon has wandered in and fouled the Great Hall.”

“And wouldn’t that have been a sight!” Snail mused, knowing that she wouldn’t have been the one to have to clean that mess up. That job belonged to the moat boys and the dragon wranglers.

But thinking about it—the fat old moat dragon humping out of the water, dripping pond scum and duckweed, shedding frogs and lily pads, lumping through the portcullis and into the courtyard, scattering the warhorses, making its loopy way into the Great Hall . . . she began to giggle.

“Snail!”

“Moving,” Snail answered as she quickly scootched around her bed, throwing off nightgown and nightcap. Fey ears were sensitive to the cold, and even though hers were rounder and shorter than most, and closer to her head, she wore a cap to bed at night. Everyone did.

“Snail!” This time there was steel in Mistress Softhands’ voice. She always called three times. Not the magical three, she always warned, but the practical three. Because it takes you three times to do what I ask.

Snail didn’t wait for a fourth call, for if it came, it would be accompanied by a switch and a spell. Usually a turn-into-a-snail spell. Not a real snail, of course. True transformations were royal magic and no one below that status could do them. But it would be an illusion that felt real enough to Snail. For a minute or more she’d look and feel like a single-footed slime creature, the size of the snail relating to how angry her mistress was at the time. Once—it was a truly awful once—she’d been turned into a dog-sized snail for an entire afternoon. Or at least she remembered it that way. Then she was set out on the lip of the castle’s well where everyone laughed at her and two of the young dukes threatened to push her in. They were only kept back from accomplishing their threat by Mistress Softhands’s secondary ward spell.

Snail knew her name was a joke, given to her when she was three years old. Before that, she had been called “Baby” and then “Child” and sometimes “Little Nuisance” and “Why Did I Bother?” And when Mistress Softhands was really angry with her, simply “You!”

Only “Snail” had stuck.

But at the moment names didn’t much matter to her. Her belly hurt from all that cake, and her rump stung from Mistress Softhands’ measuring stick, and somewhere during the night’s festivities she must have banged the back of her arm, because she could just make out a bruise blossoming there, the color of thistle.

Mistress Softhands stomped into the bedchamber, jowls aquiver, grey hair threatening to come down from her tightly wound bun, and then wouldn’t there be trouble!

Leaping off the bed, Snail cried out, “I’m up, Mistress! I’m up!”

“But not dressed.”

Mistress Softhands handed her the striped apprentice dress and white starched apron that she’d taken from the floor. She held it between her thumb and forefinger as if the thing was something stinking, something hauled out of the midden pile.

Snail accepted the dress and apron, her mouth turned down in what she hoped was a penitent’s pout.

“Not your dress on the floor again, Snail. Not today of all days.” Mistress Softhands was aroar and her face practically a wound. “What if the new princeling picks up something ghastly from this garment—a fleshbug or a nose nibbler or . . .”

Head down, her cheeks practically blistering with shame, Snail put the dress on, buttoned it up the front, then tied the apron with a knot in the back, only thinking the tying spell but not daring to say it aloud.

Mistress Softhands held her right palm toward the dress, and Snail flinched. She hated being poked in the stomach and Mistress Softhands knew it. But the midwife had no such intentions. Fingers tight together, she moved her hand in circles.

Absterge, clarify,

Launder, wash, rinse, then dry,

Dredge, dust, depurate,

Scour, scrunge, and expurgate.

All out!

On the last, with a controlled shout, she pushed her hand forward, almost—but not really—touching the dress.

Now that, Snail thought, is a proper grown-up spell. She couldn’t remember half the words and didn’t know what the other half meant. Except for wash and rinse. Oh, and dry! But now, at least, her dress was clean.

Mission accomplished, Mistress Softhands smiled, smoothed down her own starched white apron, and left the room.

ASPEN ENTERS THE HALL

Prince Aspen stood in his braies and stared into the broad chest at the foot of his bed. Tapping a finger against his cheek, he considered the neatly folded piles of cloth inside.

Linen hose today, he thought, since it is to be a celebration feast. He reached inside for a pair of periwinkle hose and pulled them on. Tying them at the top, he thought, And a linen shirt to match. He rummaged through till he found a fine linen shirt with periwinkle threading. Once he’d hefted it over his head, the shirt hung nearly to his ankles.

“Tunic,” he said aloud.

He looked at the bed, where a tunic had been laid out for him. It was a dark, drab green.

“That will never do, Lisbet,” he said to the empty room. “It doesn’t match the shirt at all. I’ll need something brighter. Perhaps in a color more . . . unexpected.” He looked in the chest and smiled. “Yes. Red.”

Sometimes in the morning, Aspen liked to pretend he was still back home and Lisbet, his old nanny, was helping him choose clothes for the day. Alone in his room, he could pretend the bustle he heard in the halls was made by brownies, not bogles or goblins, and that when he walked out the door, they would all bow to him with bright courtesy and respect and say, “Good morrow, Prince Aspen.”

Actually, he thought, the bogles and goblins all bow and say good morrow, too. He frowned. But they do it grudgingly.

Yes, he was a prince here, just like at home. But here he was also a hostage, a prisoner, a bargaining chit to keep the peace. And though the bogles and goblins bowed and scraped as they were supposed to, Aspen knew that if it came to war, their long knives would be in his belly before he could say back to them, “And good morrow to you.”

He tried to shake off that dark thought by picturing old Lisbet, but realized he couldn’t remember wh

at she actually looked like. It had been seven years since he’d last seen her, before he was sent to the Unseelie king as hostage, in exchange for one of their own. He’d been but a child then.

“And I’m still a child if I think games and imaginings will help me here.” Sighing heavily, Aspen closed the chest with a thud and picked up the green tunic.

“Drab dress for another drab day,” he said, and yanked the garment over his head. Then, without fixing his hair—a deeper gold than that of the princes of the Unseelie Court—he opened the door and stalked into the hall. He almost tumbled over a small bogle who was on his knees scrubbing the flagstones.

“Good morrow, Prince Aspen,” the creature said, somehow managing to bow even lower than he already was while still sending out waves of resentment and disdain. Aspen wanted to kick the ugly little thing. It was a sworn enemy of his people, after all.

But kicking a servant was how an Unseelie prince would behave. And I am Seelie, he reminded himself. It did no good. He had been at this court too long. Almost half his life.

“And good morrow to you, kind bogle,” he said quickly, with a shallow nod of his head, as if giving the creature back its own disdain doubled. Then he trudged down the hall toward the feast hall.

The festivities were already in full force when Aspen arrived.

The Unseelie hardly waited for a civilized hour to start carousing, as Aspen’s family would have. There was no decorum to the procedure, no stately procession of courses, no palate cleansers between. The Unseelie sat at their tables—or in some cases, on them—and celebrated rude toasts by crashing their tankards together so hard there was as much mead on the floor as in their bellies. They banged spear hafts against the table when they got angry or happy or somewhere in between, and occasionally spitted an unwary hob with the other end. It was a mob scene, unruly and loud. Almost every dinner was like this, and celebrations such as the one they were gathered for—because the queen was due to have a child at any moment—were especially loud. And dangerous. He would have to watch both his back and his stomach.

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool