- Home

- Jane Yolen

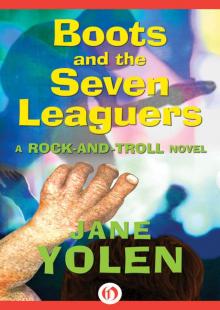

Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW—

NEW DEALS HATCH EVERY DAY!

Boots and the Seven Leaguers

A Rock-and-Roll Troll Novel

Jane Yolen

To Adam, Betsy, and the Boo (a.k.a. Alison)—

Rock and roll!

And to Michael Stearns, who loved it first.

Meet me under the bridge tonight.

We’re going to pick up a friend

Or pick a fight.

Tonight.

—“Meet Me,” from BRIDGE BOUND

CHAPTER ONE

SIGNS

There were signs all over the Kingdom, all over Erlking Hollow.

Not the usual signs, the ones full of magic and the haze of glamour.

These signs were posters announcing that Boots and the Seven Leaguers, the greatest rock-and-troll band in the world, were coming to play Rhymer’s Bridge in three days.

On the full moon.

Three days—and me without a ticket!

No ticket … and no coins to buy one. I’d spent all my pocket money on a box of magic cards. But the only magic they’d produced was a lightening of my pockets.

However, I had managed to scam one of the band’s new posters for my room. A super-realistic, gnarly, snarly full-color shot of the band.

I’d grabbed it from an alley wall near the hind end of the City, a place where I knew that no one would stop me from taking it. (Not like they would in the center of the City, where I’d have been reported to the Queen’s Men and hauled off to the Doom Room for questioning. The Queen’s Men rule the Kingdom with a heavy hand.)

That alley had been dark and scary, a gathering place for old posters and older spells. A phosphorescent green slime drizzled down the wall. Broken bottles littered the cracked pavement. There was a smell there I couldn’t quite catch.

All the kids in the Kingdom know about that alley. It’s a place of wild magic. The kind no one controls. Yeah—we all know about that alley. But few are foolish enough to go in there.

Not unless they’re desperate.

Desperation and magic—that’s a dangerous combination. It has killed some of the Folk, and many humans. But we trolls come in a large size and are made of stronger stuff. So I went in.

Just grab the poster and run, I reminded myself, though I have to admit my back was wet with the sweating fears.

I swear daylight hadn’t shone in that alley in years.

Centuries, even.

The bones of what-I-dared-not-name lay scattered in the dust. Maybe they belonged to the elf who’d put the poster there in the first place. I could just make out the bones in the shadows, a jumble of white, like the remains of somebody’s dinner.

It’s not true that nothing frightens a troll.

Dead folk give me the heebie-jeebies.

But I wanted that poster and I was determined to get it.

Besides, I figured that whoever was dead in the alley wouldn’t be going to the concert anyway, so what did he need the poster for? But just in case, I went in quick to strip the poster from the wall.

Strip—and get out of there.

The poster was stuck tighter than a ghoul’s sucker, and I had to slow down or rip it.

Behind me I could hear those bones starting to reassemble themselves, the clickety-clack of tibias and fibulas and who-knows-what-else clattering together. And a hint of dark, uncontrolled magic collecting behind the bones, giving them a push.

Whoever lay there wasn’t just dead.

He was undead.

Bad cess—even for trolls.

I worked my thumbnail under the poster and then up along the side.

Click.

Clack.

I could hear the bones nestling together, but I had half the poster off the wall and didn’t want to stop.

Clickety-clack.

And then I had it off entirely. What was underneath stopped me for a moment. It was a picture of a missing pixie child, his pointed ears drooping. He’d been squinting into the camera. But that was none of my lookout. Trolls don’t mix with pixies.

Clickety-clickety-clack.

I turned and—rolling the poster up as I ran—made for the light, moving faster than my mother would have thought possible.

Of course, I didn’t look back. I knew better than that. If I were to see the assembled bones over my left shoulder, the bones could follow me all night.

Clickety-clickety-clack-clack.

If I saw them over my right, I’d be following him. That’s the way bone magic works in the hind end of the City.

Everybody knows that.

Mr. Standing Bones clearly considered that poster his own. I could hear him as he started after me.

Click.

Clack.

Never, I thought. I’d never go back into that alley again. Not for anything. Not even for Boots and the band. Though I didn’t drop the poster.

My mouth was dry and I grabbed my breath in gulps. I ran back into the sun, where the dark couldn’t gather.

Suddenly the clicks and clacks stopped.

I didn’t turn, but I could guess. The skeleton couldn’t chase me out into the sun, the undead being shadow folk. And while trolls aren’t great fans of the sun—we go grey as ash, grey as stone, under its light—this was one time that I welcomed its warmth on my face.

Still, the sticky hand of horror lay across my back long after I hit the bright street, so I kept running another block to be sure, and ran right into the center of the City.

I stopped by the entrance to the Queen’s winter palace, unrolled the poster, and grinned.

By the Law of Finders, the poster was now mine—and it was awesome. Gnarly, snarly, indeed.

The band members were wearing all leather, with hard knobs and studded wristers, and tight leather trews. Boots had a bloodred bandanna around his black dreads and six new gold rings in his ears. Armstrong was snarling out at the camera, one hand holding her bodhran and the other clutched around a bottle of Dregs. Cal and Iggy were pretending to bite the heads off of chickens, and maybe Cal was pretending a bit too much because blood was trickling down his chin and the chicken looked really unhappy.

Which is cool.

And as usual, Booger was way off to the side of the picture looking bored.

It was the greatest poster I’d ever seen, and it was going right over my bed, whether Mom complained or not.

It’s my room, after all.

Well—my half of the room.

The other half belongs to my baby brother, Magog, who is small for his age and light for a troll and wears glasses made by a boggle, so who cares what Magog thinks. Except, Magog likes the band as much as I do.

The band comes through the Kingdom only once a year these days. Mostly they play for humans out in the Out, not for us Folk in the In. They’ve won a Grammy and a platinum record and they’re so big outside the Kingdom that they don’t need to play for the Fey anymore, except that they aren’t so big that they’ve forgotten their roots. Here. In the Kingdom.

After all, Boots was born just upriver from me, under Netherstone Bridge, which makes him kind of kin. Bridge trolls hang together, of course. The other band members are all Middle Kingdom trolls, which makes them kin as well. We trolls hold on to our kinship lines as a sacred trust. We may fight among ourselves—but don’t you try and fight against any one of us. Then you’ll have the whole lot of us to contend with.

Some of the kids say Boots and the band play the Kingdom just because they have to come here once a year or they’ll never get back In again. That staying away for an entire run of the sun locks you out of the Kingdom forever. And then t

hey’d be Out there with humans instead of In here with us Fey. Humans may have electricity, but they’ve got no power. My best friend, Pook, told me he read that in The Rules of the Kingdom.

But I didn’t believe him. He’s a pookah and as they are all tricksters and shape-changers, you can’t always trust them. Even when one’s your best friend.

I knew better anyway. The band was playing here because no matter how famous they get in the Out—the outside world—what’s really important to them is what’s In. In the Kingdom. Boots said so in an interview in People, though not in the cover story. I found the magazine floating near one of the Kingdom’s doors. It wasn’t so soaked I couldn’t dry it out and read it.

There it was in print. “I’ll always be loyal to the Kingdom,” Boots said.

So it has to be true.

And now they were going to do a one-nighter at Rhymer, just like they say on Bridge Bound, their first album. You know:

First timer,

Under Rhymer,

Where cooler waters flow.

That makes me real proud—bridges both over and under being important to us trolls, and Rhymer’s Bridge being the most important bridge in the Kingdom.

Boots and the Seven Leaguers playing under the bridge made me feel close and connected to the whole band. Almost as if I were one of them.

So I knew that somehow I was going to have to get to see them.

I just had to.

Even if I didn’t have a ticket.

Or the coins to buy one.

Yet.

You can always get something from a greenman,

But you might not like what you get.

—“Greenman,” from BRIDGE BOUND

CHAPTER TWO

GREENMAN

If I couldn’t get a ticket anywhere else, I knew I could always go to a greenman.

Of course, Mom had warned me and warned me against them. Don’t all mothers?

“Trolls,” she always says, “are an ancient race. Blah-de-blah.” (Insert your ancestry lines here. Mom always does.)

“And we never had to hang around the greenmen in the olden days.” (Read really ancient times.)

“And you shouldn’t be tempted to now, Gog. They’re just a bad lot.” (It’s the same old stuff. I stop listening almost immediately. I mean, how often can you hear about temptation, the whys and wherefores, and not want to throw up?)

When I was young and hairless and bridge-bound, having to stay close to my own bridge when not in the company of a grown-up, I wasn’t tempted by the greenmen. Not even a little. So I guess I get no awards for the straight line there.

Of course, once I had hair down past my shoulders and was old enough to go up- and downstream on my own, there was always a greenkid or two or three sitting on the riverbank, with their cool camo outfits and hawk feathers laced into their dark braids. They like to laze around and call out to anyone passing by, “Wanna try some …?” Offering up grasses of all kinds: dried rye and timothy and golden alfalfa from the Forbidden Fields.

And of course they always have tickets to whatever is coming through the Kingdom. I don’t know how, but they do.

Sure, we all know they’re a bad lot—not just tricksy like the pookahs, who might get you into trouble but would never try to hurt you. You don’t ever trust pookahs, even though you can live with them. But it’s the very badness of the Greenman and his kin that is so … well … tempting.

So, even if I didn’t actually hang with them, I hung near them. Dangerous but deliciously near.

All the kids in the Kingdom do it. It’s called banking: when you climb up on the riverbank as close to a greenkid as you dare.

But not too close, of course.

Pook told me he once banked so close to the Greenman himself—that ageless rogue—that he could count the green nose hairs.

Not that I believed Pook entirely. I mean, I didn’t even know if the Greenman has nose hairs. Or if they are green.

But I sure don’t tell my mom about banking. If I told her that, I’d never hear the end of it.

“Gog!” she’d say, her long nose wrinkling. “Only brownies are thick enough to do such a thing.”

She’d mean stupid enough, but she never uses the s-word.

Still, though I’ve banked a bit, I’ve never promised any greenkid an unspecified something, which everyone in the Kingdom knows is a totally stupid thing to do. If you promise a greenkid that way, you deserve what you get. Which is why everyone from the Out falls for greenman promises all the time, expecting to get something for nothing. Or something for very little, anyway. Outsiders—so my dad says—simply don’t have the brains of a brownie. I’ve never actually met any.

Outsiders, that is.

So, there I was, trudging back downstream to our bridge, the cold water making familiar runs around my knees. The poster was rolled tight and jammed down the front of my jerkin. I didn’t want the poster to get wet, which was why it wasn’t in my boot. And I needed both hands free, of course. Even for a troll, river walking can be rigorous when the river is in full spate—and at the full moon, all the water in the Kingdom runs high and heavy.

I was humming a tune from the Seven Leaguers’ latest CD, TrollGate. The part that goes:

Under the bridge,

Right under the span,

We wait for the night

And the sight of a man.…

Booger sings this incredible falsetto on that one, sounding like a wailing banshee. No one else can hit those notes. I don’t even try.

Since the river was running high and loud, I didn’t expect anyone to hear me singing. But this one greenkid, who must have been lying down in the high grass, suddenly stood up as I passed by.

He called out, “Hey, Gog, wanna trade?”

I knew better than to answer him, and I just flipped a hand through my hair, the troll sign for Get lost!, and passed on. He was a greenkid, after all.

“I got a ticket,” he called. His camo outfit was a dark shade of green, like the shadows under trees. He had a blue-jay feather over his left ear. “Up front at Rhymer’s Bridge.”

Which stopped me right in my tracks.

(Bad move number one.)

A greenkid can tell, just by the way you stop, what it is you want or need or are willing to pay.

Best to keep moving on.

But still … “Ticket … Up front … Rhymer’s Bridge.” Those five words were all I heard.

I turned.

(Bad move number two.)

He smiled that patented greenkid smile, part charm, part pure devilry, and held up something in his hand. It was a ticket, yellow and green. For Rhymer’s Bridge, all right.

“Wanna trade?” he asked again. The air around him shimmered and crackled, a clear warning that I ignored. Trolls avoid magic whenever possible. We can’t do it, so we don’t need it, as Mom always says.

I should have moved along—and fast.

Instead I gulped.

“What for?” I croaked.

(Bad move number three.)

The magic three.

I was stuck. Caught. Hauled in. Delivered.

“Whatcha got?” He looked meaningfully at the poster rolled tight and tucked down my jerkin.

I shrugged. One part of my brain thought that I could always find another poster.

The stupid part.

The part already under the greenkid’s glamour.

I forgot how I had gone into the alley to get this one. I forgot the alley’s dark, dank, scary feel. I forgot the green slime and the awful smell. I forgot the sound of Mr. Standing Bones scraping himself together behind me, and how I’d run into the sun, thankful to be turning grey under its rays.

But: “Ticket … Up front … Rhymer’s Bridge.”

The other part of my brain stopped working. The part that usually warns, Dumb move, Gog.

I crossed the river, clambered up onto the bank, drawing the poster out of my jerkin in one smooth move.

The greenkid he

ld out the ticket in his left hand and I got close enough to see up his nose. No green hairs. But then he was young, younger than me, even.

We traded.

Fair.

Square.

Or fair and square, according to the greenmen.

And in a twinkling the greenkid was gone, leaving only his laugh behind.

I knew that laugh. It meant I was in trouble.

When I looked at the ticket, it was for up front at Rhymer’s Bridge, all right. But it wasn’t for the full-moon show. It was for a concert that had already happened, last week, Wild Hunt. They were a Faerie fusion band, a rock-and-reel foursome: two banshees, one on fiddle and one on flute; a guitarist with the crystal blue eyes of a sidhe prince and a voice like an aging angel; and a human drummer named Robin the Adman. I had one of their CDs. They were OK. Good enough, though not a patch on Boots and his crew.

I’d been tricked, well and good.

But what had I expected?

He was a greenkid, after all.

I tore the ticket into tiny pieces and threw the pieces into the air, where they turned into strange golden butterflies that flitted away over the dark water and out of sight.

Will you go with me

Where the water swirls

High at the hip

And low at the curls?

—“Swirling Water,” from BRIDGE BOUND

CHAPTER THREE

PLANS

It could have been worse. The greenkid could have gotten my pants or my boots.

He could have gotten my teeth or my tonsils.

He could have gotten my long red hair.

Everyone in the Kingdom knows someone who’s lost such things to a greenman.

And the stupid part of it was, I knew better. I had known better all my life. But I hadn’t been paying attention, because I was hungry for something.

Greenmen thrive on that kind of hunger.

I could still hear the greenkid’s laughter as I slipped down the embankment and got back into the water.

The water felt cold. Or else I just was hot with embarrassment. I could feel every little whirl and swirl around my legs, and normally a troll hardly feels a thing.

I thought about running away to the borders where the Kingdom meets the Outside world. What was one more runaway in the dirty towns at the edge of Faerie?

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool