- Home

- Jane Yolen

A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Table of Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Introduction

The Hatchlings

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

The Snatchlings

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

The Fighters

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

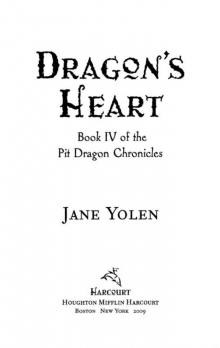

Sample Chapter of DRAGON’S HEART

Copyright © 1987 by Jane Yolen

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

First Magic Carpet Books edition 1997

First published 1987 by Delacorte Press

Magic Carpet Books is a trademark of Harcourt, Inc., registered in the United States of America and/or other jurisdictions.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Yolen, Jane.

A sending of dragons/Jane Yolen.

p. cm.—(Pit dragon chronicles; bk. 3)

“Magic Carpet Books.”

Summary: Falsely accused of sabotage, Jakkin and Akki are left to certain death in the wilderness of the planet Austar IV but, with the aid of five baby dragons, manage not only to survive but also

to gain unusual powers and insights.

[1. Dragons—Fiction. 2. Fantasy.] I. Title.

PZ7.Y78Sd 2004

[Fic]—dc22 2003056662

ISBN-13: 978-0152-05128-0 ISBN-10: 0-15-205128-7

Illustration by Tom McKeveny

eISBN 978-0-547-54476-2

v2.0215

For Jonathan Grenzke,

dragon master,

shatterer of a thousand shields,

who lives right down the road

AUSTAR IV is the fourth planet of a seven-planet rim system in the Erato Galaxy. Once a penal colony, marked KK29 on the convict map system, it is a semi-arid, metal-poor world with two moons.

Austar is covered by vast deserts, some of which are cut through by small, irregularly surfacing hot springs, several small sections of fenlands, and zones of what were long thought to be impenetrable mountains charted only by the twice-yearly flyovers by Federation ships. There are only five major rivers: the Narrakka, the Rokk, the Brokk-bend, the Kkar, and the Left Forkk.

Few plants grow in the deserts: some fruit cacti and sparse long-trunked palm trees known as spikka. The most populous plants on Austar are two wild-flowering bushes called burnwort and blisterweed. (See color section.) The mountain vegetation, only recently studied, is varied and includes many edible fungi, berry bushes, and a low oily grass called skkagg, which, when boiled, produces a thin broth high in vitamin content.

There is a variety of insect and pseudolizard life, the latter ranging from small rock runners to elephant-sized dragons. (See holo sections, vol. 6.) Unlike Earth reptilia, the Austarian dragon-lizards are warm-blooded, with pneumaticized bones for reduction of weight and a keeled sternum where the flight muscles are attached. They have membranous wings with jointed ribs that fold back along the animals’ bodies when the dragons are earthbound. Stretched to the fullest, an adult dragon’s wings are twice its body size. The “feathers” are actually light scales which adjust to wind pressure. From claw to shoulder, some specimens of Austarian dragons have been measured at thirteen feet. There is increasing evidence of a level 4+ intelligence and a color-coded telepathic mode of com munication in the Austarian dragons. These great beasts were almost extinct when the planet was first settled by convicts (or KKs as they called themselves) and guards from Earth in 2303. But several generations later the Austarians domesticated the few remaining dragons, selectively breeding them for meat and leather and the gaming arenas—or, as they were known from earliest times, the pits.

The dragon pits of Austar IV were more than just the main entertainment for early KKs. Over the years the pits became central to the Austarian economy. Betting syndicates developed, and Federation starship crews on long rim-world voyages began to frequent the planet on gambling forays.

Because such gambling violated current Galaxian law, illegal offworld gamesters were expelled in 2485 from Austar IV and imprisoned on penal planet KK47, Sedna, a mining colony where most of the surface is ice covered. Under pressure from the Federation, the Austarians then drafted a Protectorate constitution spelling out the Federation’s administrative role in the economy of the planet, including regulation of the gambling of offworlders and the payment of taxes (which Austarians call tithing) on gambling moneys in exchange for starship landing bases. A fluid caste system of masters and bond slaves—the remnants of the convict-guard hierarchy—was established by law, with a bond price set as an entrance fee into the master class. Established at the same time was a Senate, the members of which come exclusively from the master class. The Senate performs both the executive and legislative functions of the Austarian government and, for the most part, represents all the interests of the Federation in Austarian matters. As with all Protectorate planets, offworlders are subject to the local laws and liable to the same punishments for breaking them.

The Rokk, which was a fortress inhabited by the original ruling guards and their families when Austar IV was a penal planet, is now the capital city and the starship landfall.

In the mid-2500s disgruntled bonders, angry with their low place in Austarian society and the inequities visited upon their class, began to foment a revolution, which broke into violent confrontations. The worst of these was the bombing of Rokk Major, the greatest gam ing pit on the planet. Thirty-seven people were killed outright; twenty-three died of their wounds in the months that followed. Hundreds of other people, both Austarians and offworlders, were seriously injured. It was the beginning of several years of internal conflict which, according to Federation rules, led to the closing of Austar to Federation ships by means of a fifty-year embargo. This embargo was imposed in 2543 and kept all official ships from landing, which meant Austar IV was without sanctioned metal and technical assistance for that period of time. Occasional pirate ships slipped through the embargo lines, and intercepted coded transmissions from the ships indicate that there is more than the simple expected master—bonder power struggle being waged on the planet. Frequent references to Dragon Masters and Dragonmen remain unclear. The complete story of Austar IV will probably not be known until the Federation embargo is lifted and the Austarians speak for themselves.

—excerpt from The Encyclopedia Galaxia,

thirty-second edition, vol. I:

Aaabarker—Austar

The Hatchlings

1

NIGHT WAS APPROACHING. The umber moon led its pale, shadowy brother across the multicolored sky. In front of the moons flew five dragons.

The first was the largest, its great wings dipping and rising in an alien semaphore. Directly behind it were three smaller fliers, wheeling and circling, tagging one another’s tails. In the rear, along a lower trajectory, sailed a middle-sized and plumper version of the front drag

on. More like a broom than a rudder, its tail seemed to sweep across the faces of the moons.

Jakkin watched them, his right hand shading his eyes. Squatting on his haunches in front of a mountain cave, he was nearly naked except for a pair of white pants cut off at midthigh, a concession to modesty rather than a help against the oncoming cold night. He was burned brown everywhere but for three small pits on his back, which remained white despite their long exposure to the sun. Slowly Jakkin stood, running grimy fingers through his shoulder-length hair, and shouted up at the hatchlings.

“Fine flying, my friends!” The sound of his voice caromed off the mountains, but the dragons gave no sign they heard him. So he sent the same message with his mind in the rainbow-colored patterns with which he and the dragons communicated. Fine flying. The picture he sent was of gray-green wings with air rushing through the leathery feathers, tickling each link. Fine flying. He was sure his sending could reach them, but none of the dragons responded.

Jakkin stood for a moment longer watching the flight. He took pleasure in the hatchlings’ airborne majesty. Even though they were still awkward on the ground, a sure sign of their youth, against the sky they were already an awesome sight.

Jakkin took pleasure as well in the colors surrounding the dragons. Though he’d lived months now in the Austarian wilds, he hadn’t tired of the evening’s purples and reds, roses and blues, the ever changing display that signaled the approaching night. Before he’d been changed, as he called it, he’d hardly seen the colors. Evenings had been a time of darkening and the threat of Dark-After, the bone-chilling, killing cold. Every Austarian knew better than to be caught outside in it. But now both Dark-After and dawn were his, thanks to the change.

“Ours!” The message invaded his mind in a ribbon of laughter. “Dark-After and dawn are ours now.” The sending came a minute before its sender appeared around a bend in the mountain path.

Jakkin waited patiently. He knew Akki would be close behind, for the sending had been strong and Akki couldn’t broadcast over a long range.

She came around the bend with cheeks rosy from running. Her dark braid was tied back with a fresh-plaited vine. Jakkin preferred it when she let her hair loose, like a black curtain around her face, but he’d never been able to tell her so. She carried a reed basket full of food for their dinner. Speaking aloud in a tumble of words, she ran toward him. “Jakkin, I’ve found a whole new meadow and..

He went up the path to meet her and dipped his hand into the basket. Before she could pull it away, he’d snagged a single pink chikkberry. Then she grabbed the basket, putting it safely behind her.

“All right, worm waste, what have you been doing while I found our dinner?” Her voice was stem, but she couldn’t hide the undercurrent of thought, which was sunny, golden, laughing.

“I’ve been working, too,” he said, careful to speak out loud. Akki still preferred speech to sendings when they were face-to-face. She said speech had a precision to it that the sendings lacked, that it was clearer for everything but emotions. She was quite fierce about it. It was an argument Jakkin didn’t want to venture into again. “I’ve some interesting things—”

Before he could finish, five small stream- like sendings teased into his head, a confusion of colored images, half-visualized.

“Jakkin . . . the sky . . . see the moons . . . wind and wings, ah . . . see, see . . .”

Jakkin spun away from Akki and cried out to the dragons, a wild, high yodeling that bounced off the mountains. With it he sent another kind of call, a web of fine traceries with the names of the hatchlings woven within: Sssargon, Sssasha, and the triplets Tri-sss, Tri-ssskkette, and Tri-sssha.

“Fewmets!” Akki complained. “That’s too loud. Here I am, standing right next to you, and you’ve fried me.” She set the basket down on an outjut of rock and rubbed her temples vigorously.

Jakkin knew she meant the mind sending had been too loud and had left her with a head full of brilliant hot lights. He’d had weeks of similar headaches when Akki first began sending, until they’d both learned to adjust. “Sorry,” he whispered, taking a turn at rubbing her head over the ears, where the hot ache lingered. “Sometimes I forget. It takes so much more to make a dragon complain and their brains never get fried.”

“Brains? What brains? Everyone knows dragons haven’t any brains. Just muscle and bone and . . .”

“. . . and claws and teeth,” Jakkin finished for her, then broke into the chorus of the pit song she’d referred to:

Muscle and bone

And claws and teeth,

Fire above and

Fewmets beneath.

Akki laughed, just as he’d hoped, for laughter usually bled away the pain of a close sending. She came over and hugged him, and just as her arms went around, the true Austarian darkness closed in.

“You’ve got some power,” Jakkin said. “One hug—and the lights go out!”

“Wait until you see what I do at dawn,” she replied, giving a mock shiver.

To other humans the Austarian night was black and pitiless and the false dawn, Dark-After, mortally cold. Even an hour outside during that time of bone chill meant certain death. But Jakkin and Akki were different now, different from all their friends at the dragon nursery, different from the trainers and bond boys at the pits, different from the men who slaughtered dragons in the stews or the girls who filled their bond bags with money made in the baggeries. They were different from anyone in the history of Austar IV because they had been changed. Jakkin’s thoughts turned as dark as the oncoming night, remembering just how they’d been changed. Chased into the mountains by wardens for the bombing of Rokk Major, which they had not really committed, they’d watched helplessly as Jakkin’s great red dragon, Heart’s Blood, had taken shots meant for them, dying as she tried to protect them. And then, left by the wardens to the oncoming cold, they had sheltered in Heart’s Blood’s body, in the very chamber where she’d recently carried eggs, and had emerged, somehow able to stand the cold and share their thoughts. He shut the memory down. Even months later it was too painful. Pulling himself away from the past, he realized he was still in the circle of Akki’s arms. Her face showed deep concern, and he realized she’d been listening in on his thoughts. But when she spoke it was on a different subject altogether, and for that he was profoundly grateful.

“Come see what I found today,” she said quietly, pulling him over to the basket. “Not just berries, but a new kind of mushroom. They were near a tiny cave on the south face of the Crag.” Akki insisted on naming things because—she said—that made them more real. Mountains, meadows, vegetations, caves—they all bore her imprint. “We can test them out, first uncooked and later in with some boil soup. I nibbled a bit about an hour ago and haven’t had any bad effects, so they’re safe. You’ll like these, Jakkin. They may look like cave apples, but I found them under a small tree. I call them meadow apples.”

Jakkin made a face. He wasn’t fond of mushrooms, and cave apples were the worst.

“They’re sweeter than you think.”

Anything, Jakkin thought, would be sweeter than the round, reddish cave apples with their musty, dusty taste, but he worried about Akki nibbling on unknown mushrooms. What if they were poisonous and she was all alone on the mountainside?

Both thoughts communicated immediately to Akki and she swatted him playfully on the chest. “Cave apples are good for you, Jakkin. High in protein. I learned that from Dr. Henkky when I studied with her in the Rokk. Besides, if I didn’t test these out, we might miss something good. Don’t be such a worrier. I checked with Sssasha first and she said dragons love them.”

“Dragons love burnwort, too,” muttered Jakkin. “But I’d sure hate to try and eat it, even if it could help me breathe fire.”

“Listen, Jakkin Stewart, it’s either mushrooms—or back to eating dragon stew. We have to have protein to live.” Her eyes narrowed.

Jakkin shrugged as if to say he didn’t care, but his thoughts broadca

st his true feelings to her. They both knew they’d never eat meat again. Now that they could talk mind-to-mind with Heart’s Blood’s hatchlings and even pass shadowy thoughts with some of the lesser creatures like lizards and rock-runners, eating meat was unthinkable.

“If meadow apples are better than cave apples,” Jakkin said aloud, “I’m sure I’ll love them. Besides, I’m starving!”

“You and the dragons,” Akki said. “That’s all they ever think about, too. Food, food, food. But the question is—do you deserve my hard-found food?”

“I’ve been working, too,” Jakkin said. “I’m trying to make some better bowls to put your hard-found food in. I discovered a new clay bank down the cliff and across Lower Meadows. You know . . .”

Akki did know, because he never went near Upper Meadows, where Heart’s Blood’s bones still lay, picked clean by the mountain scavengers. He went down toward the Lower Meadows and she scouted farther up. He could read her thoughts as clearly as she could read his.

He continued out loud, “. . . there’s a kind of swamp there, the start of a small river, pooling down from the mountain streams. The mountain is covered with them. But I’d never seen this particular one before because it’s hard to get to. This clay is the best I’ve found so far and I managed a whole sling of it. Maybe in a night or two we can build a fire and try to bake the pots I’ve made.”

They both knew bake fires could be set only at night, later than any humans would be out. Just in case. Only at night did they feel totally safe from the people who had chased them into the mountains: the murderous wardens who had followed them from the bombed-out pit to the dragon nursery and from there up into the mountains, and the even more murderous rebels who, in the name of “freedom,” had fooled them into destroying the great Rokk Major Dragon Pit. All those people thought them dead, from hunger or cold or from being crushed when Heart’s Blood fell. It was best they continue to believe it. So the first rule of mountain life, Jakkin and Akki had agreed, was Take no chances.

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool