- Home

- Jane Yolen

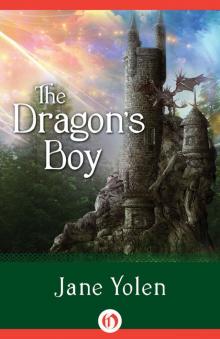

The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy Read online

The Dragon’s Boy

Jane Yolen

For David, in memory of our months in Scotland,

and Heidi, Adam, and Jason, who stayed at home,

getting wisdom.

Contents

1 The Cave in the Fens

2 The Master of Wisdoms

3 Home Again

4 Conversation in the Smithy

5 The Getting of Wisdom

6 The Getting of a Sword

7 Days of Wisdom

8 Day of the Sword

9 Friends

10 At the Fairs

11 Son of the Dragon

12 The Dragon’s Boy

A Note from the Author

A Biography of Jane Yolen

1

The Cave in the Fens

IT WAS ON A DAY in early spring, with the clouds scudding across a gray sky, promising a rain that never quite fell, that Artos found the cave.

“Hullo,” he whispered to himself, a habit he’d gotten into as he so often had no one else to talk to.

He hadn’t been looking for a cave but rather chasing after Sir Ector’s brachet hound Boadie, the one who always slipped her chain to go after hare. She’d slipped Artos as well, speeding down the cobbled path and out the castle’s small back gate, the Cowgate. Luckily he’d caught sight of her as she whipped around the corner of it, and on and off he’d seen her coursing until they’d come to the boggy wasteland north of the castle. Then he’d lost her for good and could only follow by her tracks.

If she hadn’t been Sir Ector’s prize brachet and ready to whelp for the first time, he’d have left her there and trudged back to the castle in disgust, knowing she’d eventually find her way home, with or without any hare. But he feared she might lose her pups out there in the bogs, and then he’d get whipped double, once for letting her get away and once for the loss of the litter. So he spent the better part of the morning following her tracks, crossing and recrossing a small, cold, meandering stream and occasionally wading thigh deep in the water.

He let out his own stream of curses, much milder than any the rough men in the castle used. But they were heartfelt curses against both the chill of the water and the fact that, if he’d been one of the other boys—Bedvere or Lancot or Sir Ector’s true son, Cai—the water would have only been up to his knees. They’d all gotten their growth earlier than he. Indeed, despite Sir Ector’s gruff promises that he would be tallest of them all, Artos despaired of ever getting any bigger. At thirteen surely he deserved to be higher than Lady Marion’s shoulder.

“Knees or thighs,” he reminded himself, unconsciously mimicking Sir Ector’s mumbling accent, “it’s blessed cold.” He climbed out of the stream and up the slippery bank.

Despite the cold, his fair hair lay matted with sweat against the back of his head, the wet strands looking nearly black. There was a streak of mud against the right side of his nose, deposited there when he’d rubbed his eye with a grimy fist. His cheeks, naturally pale, were flushed from the run.

The sun was exactly overhead, its corona lighting the edges of the clouds. Noon—and he hadn’t eaten since breakfast, a simple bowl of milk swallowed hastily before the sun was even up. His stomach growled at the thought. Rubbing a fist against his belly to quiet it, he listened for the hound’s baying.

It was dead still.

“I knew it!” he whispered angrily. “She’s gone home.” He could easily imagine her in the kennel-yard, slopping up food, her feet and belly dry. The thought of being dry and fed made his own stomach yowl again. This time he pounded against it three times. The growling stopped.

Nevertheless, the brachet was his responsibility. He had to search for her till he was sure. Putting his fingers to his mouth, he let out a shrill whistle that ordinarily would have brought Boadie running.

There was no answer, and except for the sound of the wind puzzling across the fenland, there was a complete silence.

The fen was a low, hummocky place full of brown pools and quaking mosses; and in the slow, floating waters there was an abundance of duckweed and frog-bit, mile after mile of it looking the same. From where he stood, low down amongst the lumpy mosses, he couldn’t see the castle, not even a glimpse of one of the two towers. And with the sun straight overhead, he wasn’t sure which way was north or which way south.

Not that he thought he was lost.

“Never lost—just bothered a bit!” he said aloud, using the favorite phrase of the Master of Hounds, a whey-colored man with a fringe of white hair. The sound of the phrase comforted him. If he wasn’t lost—only bothered—he’d be home soon, his wet boots off and drying in front of a warm peatfire.

Turning slowly, Artos stared across the fens. His boots were sinking slowly in the shaking, muddy land. It took an effort to raise them, one after another. Each time he did, they made an awful sucking noise, like the Master of Hounds at his soup, only louder. At the last turn, he saw behind him a small tor mounding up over the bog, dog tracks running up it.

“If I climb that,” he encouraged himself, “I’ll be able to see what I need to see.” He meant, of course, he’d be able to see the castle from the small hillock and judge the distance home, maybe even locate a drier route. His feet were really cold now, the water having gotten in over the tops of his boots in the stream and squishing up between his toes at every step. Not that the boots mattered. They were an old pair, Cai’s castoffs, and had never really fit anyway. But he still didn’t fancy walking all the way back squishing like that.

He’d never been on his own this far north of the castle before and certainly never would have planned coming out into the watery fens where the peat hags reigned. They could pull a big shire horse down, not even bothering to spit back the bones. Everyone knew that.

“Blasted dog!” he swore again, hotly. “Blasted Boadie!” He felt a little better having said it aloud.

If the little tor had been a mountain he wouldn’t have attempted it. Certainly neither he nor any of the other boys would dare go up the High Tor, which was the large mount northwest of the castle. It was craggy, with sheer sides, its top usually hidden in the mists. There was no easy path up. The High Tor had an evil reputation, Cai said. Princes who tried to climb it were still there, locked in the stone. Lancot said he’d heard how the High King’s only son had been whisked away there the day he’d been born and devoured by witches for their All Hallow’s meal. Bedvere had only recently recalled a rhyme his old Nanny Bess had taught him: “Up the Tor, Life’s nae more.”

But of course the hillock wasn’t that tor and it would be the perfect place from which to get his bearings. So he slogged toward it, threading through the hummocks and the tussocky grass, forcing himself not to mind the water squishing up between his toes, following the tracks.

He was halfway up the tor and halfway around it as well when he saw the cave.

“Hullo!” he whispered.

It was only an unprepossessing black hole in the rock and only a bit higher than himself, as round and as smooth as if it had been carved out by a master hand. The opening was shaped into a rock that was as gray and slatey as the sky. There wasn’t a single grain or vein running across the rockface to distinguish it, and Boadie’s tracks had disappeared.

Nervously he ran his fingers through the tangles of his hair, his gooseberry-colored eyes wide. Then he stepped through the dark doorway. He went less out of courage than curiosity, being particularly careful of some long, spearlike rocks hanging from the ceiling of the cave just two steps beyond the opening.

Slowly his eyes got used to the dark and he began to make out a grayer, mistier color from the black. Suddenly forgetting dog and castle and the mud in his boots, he thought he might have a go at exploring. The Master of Hounds had always war

ned him that he’d a “big bump of curiosity,” as if that were a particularly bad thing to own. But, he reasoned, if you’re the youngest and the slightest, what else do you have of any use except imagination and curiosity? And so thinking, he stepped even farther into the cave.

That was when, standing ever so quiet and trying to make out the outlines of the place, he heard the breathing. At first he thought it was his own. But when he took a deep gulp of air and held it, the sound still went on. It wasn’t very loud, except that the cave had a strange magnifying power, and so he was able to hear every rumbling bit of it. It was low and steady, almost like a cat’s purr, except there was an occasional pop! serving as punctuation. It was—he was quite sure—a snore. And he knew from that snore that whatever made it had to be very large. He also knew that the Master of Hounds had been quite right in warning him about his curiosity. Suddenly he had quite enough of exploring.

He began to back out of the cave slowly, quietly, when he came bang up against something that smacked his head hard. And though he managed not to cry out, the stone rang in what seemed to be twenty different tones and, abruptly, the snore stopped.

“Blast!” Artos swore under his breath. He put a hand to the back of his head, which hurt horribly, and one in front of him to ward off whatever it was that was attached to that loud, breathy snore; for whatever it was was surely awake now.

“STAAAAAAAAY!” came a low, rumbling command.

He stopped at once and, for a stuttering moment, so did his heart.

2

The Master of Wisdoms

BEFORE ARTOS COULD MOVE, that awful voice began again.

“Whooooooooo are you?” It was less an echo this time and more an elongated sigh.

Biting his lip, Artos answered in a voice that broke several times in odd places. “I am nobody, really, just Artos. A fosterling. From Sir Ector’s castle.” He turned slightly and gestured toward the cave entrance, outside, where presumably the castle still stood. He turned back and added, hastily, “Sir.”

A low rumbling, more like another snore than a sentence, was all that answered him. It was such a surprisingly homey sound that it freed him of his terror long enough to ask, “And who are you?” He hesitated. “Sir?”

Something creaked. There was an odd clanking. Then the voice, augmented almost tenfold, boomed at him: “I AM THE GREAT RIDDLER. I AM THE MASTER OF WISDOMS. I AM THE WORD AND I AM THE LIGHT. I WAS AND AM AND WILL BE.”

Artos nearly fainted from the noise. He put his right hand before him as if to hold back the overpowering sound and bit his lip again. This time he drew blood. Wondering if blood would arouse the beast further, he sucked it away quickly. Then, when the echoes of that ghastly voice ended, Artos whispered, “Are you a hermit, sir? An anchorite? Are you a Druid priest? A penitent knight?” He knew such beings sometimes inhabited caves, but even he knew the guesses were stupid for that great noise was surely no mere man’s voice. However, he hoped that by asking he might encourage whatever it was to some kind of gentleness. Or pity.

The great whisper that answered him came in a rush of wind: “I Am The Dragon!”

“Oh!” Artos said.

“Is that all you can say?” the dragon asked peevishly. “I tell you I Am The Dragon and all you can answer is oh?”

Artos was silent.

The great breathy voice sighed. “Sit down, boy. It’s been a long time since I’ve had company in my cave. A long time and a lonely time.”

Artos was sure that the one thing he’d better not do was sit. Sitting would make him vulnerable, an easy prey. Sitting could be prelude to…to…but here his vaunted imagination failed him. All he could do was stutter. “But…but…but…” It was not a good beginning.

“No buts,” said the dragon.

“But,” Artos began again, desperately needing to uphold his end of the conversation. A talking dragon, he told himself, is not an eating dragon. Perhaps if I explain that I am sure to be missed back at the castle, now, this very moment…

“Shush boy, and listen. I will pay for your visit.”

Artos sat, plunking himself down on a small riser of stone. It wasn’t greed that kept him there. Rather, it was the thought that if he was to be paid, then hunger wasn’t the dragon’s object and therefore he, Artos, was not to be dinner.

“So, young Artos of Sir Ector’s castle, how would you like to be paid—in gold, in jewels, or in wisdom?”

A sudden flame from the center of the cave lit up the interior and, for the first time, Artos could see that there were jewels scattered about the floor amongst the rocks and pebbles. Jewels! But then, as suddenly as the flame, came the terrible thought: Dragons are known to be the finest games players in the world. It has named itself The Great Riddler. Perhaps if I don’t answer correctly, I’ll be eaten after all.

Artos could feel sweat running down the back of his neck. His feet, so long forgotten, felt squishy and cold inside the wet boots. He had a strange ache at the base of his skull, a throbbing at his temple. But then cunning, an old habit, claimed him. Like most small people, he had a genius for escape. Rarely had the bigger boys played more than one trick on him, though he’d never gotten his own back against them.

“Wisdom, sir,” he said. It was the least likely to appeal to a greedy sort, and therefore most likely to be the right answer, though he’d really rather have had gold or jewels. “Wisdom.”

Another bright flame spouted from the cave center. “An excellent choice,” the dragon said.

Artos let himself relax but only a little, for he hardly expected the game would be won this easily.

“Excellent,” the dragon repeated. “And I’ve been needing a boy just your age for some time.”

Not to eat! Artos thought wildly. Perhaps I’d better point out how small I am, how thin.

But the dragon went on as if it had no idea of the terror it had just instilled in Artos. “A boy to pass my wisdom on to. So listen well, young Artos of Sir Ector’s castle.”

Artos didn’t move and hoped the dragon wouldn’t notice how everything—everything—about him had suddenly, inexplicably, relaxed. Perhaps the dragon would take the silence to mean that Artos was listening when Artos knew it really meant that he couldn’t have moved now even if he wanted to. His hands were limp, his feet were limp, even his nose felt limp. He could scarcely breathe through it. All he could do was listen.

“My word of wisdom for the day,” the dragon began, “is this: Old dragons like old thorns can still prick. And I am a very old dragon. So take care.”

Limply, Artos whispered back, “Yes, sir.” But a part of him worried over that wisdom, picking away at it as if it were a bit of torn skin next to a fingernail. It was familiar, that wisdom. Why was it so familiar? And then he had it: The dragon’s wisdom was very similar to a bit of wit he’d heard often enough on the village streets, only there it went slightly differently. It was old priests, not old dragons, the villagers warned about. He couldn’t for the life of him think why the two should be the same. For the life of him. That, he knew, was a bad phrase at a time like this. Aloud, all he said was, “I shall remember, sir.”

“Good. I’m sure you will,” the dragon said. “And now, as a reward…”

“A reward?” He spoke without thinking.

“A reward for being such a good listener. You may take that small jewel—there.”

The strange clanking accompanied the extension of a gigantic scaled foot. The foot had four toes each the size of Artos’ thighs; there were three toes in the front, one in the back. The foot scrabbled along the cave floor, clacketing and rattling, then stopped close to Artos.

Too close, he thought, but he was too terrified to stand up and run, though inside he drew himself as far away from the foot as was possible, a kind of mental shrinking.

The nail from the center toe began to extend outward. It was a curved, steel-colored blade, reflecting in the light of the dragon’s fiery breath. It stopped with an odd click, then tapped a red j

ewel the size of a leek bulb.

“There!” the dragon said again. “Go on, boy. Take it.”

Wondering if this were yet another test, Artos hesitated and the dragon made a garumphing kind of sound deep down in its throat. Fearing the worst, Artos stood and edged toward the jewel and the horrible sword-sized nail that hovered right above it. Leaning over suddenly, he grabbed up the jewel and scuttered back to the cave entrance, breathing loudly.

“I will expect you tomorrow,” the dragon said. “You will come during your time off.”

Turning, Artos asked over his shoulder, “How do you know I have any?”

“Half an hour after breakfast and two hours at midday and all day every seventh day for the Sabbath, except right before the evening meal,” said the dragon.

“But how…?” Artos was astonished because it was true; those were the hours he had off.

“When you become as wise as a dragon, you will know these things.”

Artos sighed.

“Now listen carefully. There is a quicker path back than the way you came, clambering over the hags and half up to your navel in cold water.”

Artos did not ask how the dragon knew about his earlier journey.

“Turn right when you leave the cave and go around the big rock. There is a path straight to the Cowgate. Discover it. And tomorrow, when you come again, you will bring me stew. With meat!”

The nail was sheathed with a grinding sound, and the flame from the dragon’s hidden mouth flared up one last time as if to light Artos’ way out. Then the giant foot withdrew into the darkest part of the cave, clattering as it went.

Just as Artos turned to dash into the light, the wheezy, booming voice came again, filling the cave with echoes.

“Promise, boy. Toooooooomooooooorow.”

“Tomorrow,” Artos cried back. “I promise.” But he didn’t mean a word of it.

3

Home Again

AS HE HURRIED FROM the cave, Artos’ mind was a maelstrom of thoughts. Dragon and jewel were topmost of course, swirling about in a red fury. But right below, he worried about the brachet hound in a kind of gray mist. Hidden farther down in the blacker shadows were his anxieties about the long, uncomfortable journey back across the hummocky fens. And beneath it all was the black fear that he’d be punished for staying away so long from his duties. Not once, however, did he reconsider the promise he’d made to the dragon. Made in haste and under terrible duress, it wasn’t the kind of promise one needed to keep.

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool