- Home

- Jane Yolen

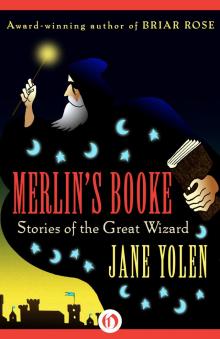

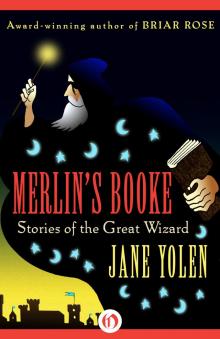

Merlin's Booke

Merlin's Booke Read online

Merlin’s Booke

Thirteen Stories and Poems about the Arch-Mage

Jane Yolen

For Terri and Mark

AND WITH SPECIAL THANKS to Emma Bull, Father Robert Coonan, John Crowley, Charles de Lint, Ed Ferman, Bob Frazier, Dr. Justina Gregory, Dr. Vernon Harward, Zane Kotker, Patricia MacLachlan, Robin McKinley, Shulamith Oppenheim, Ann Turner, Will Shetterly, Susan Shwartz, Andrew Sigel, all of whom played some part in the magic show, and especially and always for the arch-mage himself, David Stemple.

Contents

Introduction: Hic Jacet Merlinnus

The Ballad of the Mage’s Birth

The Confession of Brother Blaise

The Wild Child

Dream Reader

The Annunciation

The Gwynhfar

The Dragon’s Boy

The Sword and the Stone

Merlin at Stonehenge

Evian Steel

In the Whitethorn Wood

Epitaph

L’Envoi

Acknowledgments

A Note from the Author

A Biography of Jane Yolen

Introduction

Hic Jacet Merlinnus

WHEN THE GLASTONBURY TOMB Reputed to belong to Arthur and Guenevere was opened in the twelfth century by impecunious monks, only bones remained in the strong oak casket. That tomb—marked HIC JACET SEPULTUS INCLITUS REX ARTHURIUS IN INSULA AVALONIA, if you believe the seventeenth century antiquary Camden or HIC JACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS if you favor Sir Thomas Malory—was long a favorite touchstone of the pseudo-scholars. And, so the legend continued, alongside the bones was a tress of braided hair yellow as golde which, as soon as it was touched, turned to dust.

No tomb for the mage Merlin or Myrddin has ever been found.

Still the figure of the shape-changer, Druid high priest, wizard extraordinaire, counselor to kings bestrides the story of Arthur and his court like a colossus. Merlin’s own part in the legendary history is culled from sources as diverse as Malory; the thirteenth century Burgundian poet Robert de Boron; the scholar Geoffrey of Monmouth of twelfth century Oxford; Nennius; Wace; a variety of folktales from Scotland, Wales, Ireland, France; and bits that have traveled from as far away as India and Jerusalem. That history begins with a strange birth in a nunnery, continues through Merlin’s childhood talents as a seer for King Vortigern, through the tales of a wild, mad Welshman living in the wood of Celyddon, through the troubling prophesies sometimes credited to Nostradamus, and ends in an enchanted sleep in the forest of Broceliande. In between the folk mind has gifted the mage with powers to move stones and to transform a rough, bearish military commander into a great good king of Christendom.

Merlin’s greatest power, though, is that centuries of listeners and readers have believed in him. They believed in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s version, in Sir Thomas Malory’s version, in T.H. White’s version, in Mary Stewart’s version—even though the Merlin in each of these and hundreds of other recreations is never the same. But then was not Merlin a shape-shifter, a man of shadows, a son of an incubus, a creature of mists? There is not one Merlin, but a multitude, some dark, some light, some mystical and some substantial. Merlin is our magic mirror.

And so you have in your hands a book in which Merlin wears many faces and shapes. He is set in no one time and walks through a landscape now real, now unreal. This is revisionist mythology, stories and poems I wrote over a period of almost five years.

It is important to remember that the only thing to link these stories is the figure of Merlin and he is a different character in each tale. This is not a novel but a series of stories, each looking in toward the mage. But whether it is Merlin as seen through the eyes of the priest who baptized him in “The Confession of Brother Blaise” or through the cynical eyes of a minstrel who recreates the tale in “The Gwynhfar” or through the amnesiac eyes of the feral boy in “The Wild Child,” or through the rheumy eyes of the old magician beguiled and ensorceled in the tree in “In the Whitethorn Wood,” or through a reporter’s notes in “Epitaph,” it is the arch-mage seen, as he has always been seen, through a storyteller’s eyes, a dreamer’s eyes.

The facts about Merlin are few, the spyglass of history being both corrupted and purified by its mythic lens. Yes, there were priests and seers, shanachies and wizards, counselors of war and teachers of Latin in the times past. And some of them may have actually been involved with The Matter of Britain. But what is actual is not necessarily what is true. Merlin was all of these—priest, seer, shanachie, wizard, counselor, and teacher. And he was none of them. He is rather a character touched by fancy. And:

Tell me where is fancy bred,

Or in the heart or in the head?

The answer is, of course, both.

Jane Yolen

Phoenix Farm

Hatfield, Massachusetts

1986

“Many of those who shall read this book or shall hear it read will be the better for it, and will be on their guard against sin.”

—the infant Merlin to his confessor, Father Blaise in Vita Merlini by Geoffrey of Monmouth

The Ballad of the Mage’s Birth

The maiden sits upon the stair,

(The power’s in the stone)

And births a son twixt earth and air,

(Touch magic, pass it on.)

And at her feet a burning tree,

(The magic’s in the stone)

That is as green as green can be,

(Touch magic, pass it on).

And at her back a mossy well,

(The glory’s in the stone)

For water does complete the spell,

(Touch magic, pass it on).

Earth, air, fire, water—words—

(The naming’s in the stone)

Attend the infant mage’s birth,

(Touch magic, pass it on).

She leaves him there, still bright with blood,

(The dying’s in the stone)

Hard by the green and burning wood,

(Touch magic, pass it on).

“On my faith,” said she, “I know now. Only daughter was I to the king of Demetia. And when still young, I was made a nun in the church of Peter in Carmarthen. And as I slept among my sisters, in my sleep I saw a young man who embraced me; but when I awoke, there was no one but my sisters and myself. After this I conceived and when it pleased God the boy you see there was born. And on my faith in God, more than this never was between a man and myself.”

—Historia Regum Britanniae

by Geoffrey of Monmouth

The Confession of Brother Blaise

Osney Monastery, January 13, 1125

THE SLAP OF SANDALS along the stone floor was the abbot’s first warning.

“It is Brother Blaise.” The breathless news preceded the monk’s entrance as well. When he finally appeared, his beardless cheeks were pink both from the run and the January chill. “Brother Geoffrey says that Brother Blaise’s time has come.” The novice breathed deeply of the wood scent in the abbot’s parlor and then, because of the importance of his message, he added the unthinkable. “Hurry!”

It was to the abbot’s everlasting glory that he did not scold the novice for issuing an order to the monastery’s head as a cruder man might have done. Rather, he nodded and turned to gather up what he would need: the cruse of oil, his stole, the book of prayers. He had kept them near him all through the day, just in case. But he marked the boy’s offense in the great register of his mind. It was said at Osney that Abbot Walter never forgot a thing. And that he never smiled.

They walked quickly across the snow-dusted courtyard. In the summer those same whitened borders blossomed with herbs and berry bushes, adding

a minor touch of beauty to the ugly stone building squatting in the path before them.

The abbot bit his lower lip. So many of the brothers with whom he had shared the past fifty years were housed there now, in the stark infirmary. Brother Stephen, once his prior, had lain all winter with a terrible wasting cough. Brother Homily, who had been the gentlest master of boys and novices imaginable, sat in a cushioned chair blind and going deaf. And dear simple Brother Peter-Paul, whose natural goodness had often put the abbot to shame, no longer recognized any of them and sometimes ran out into the snow without so much as a light summer cassock between his skin and the winter wind. Three others had died just within the year gone by, each a lasting and horrible death. He missed every one of them dreadfully. The worst, he guessed, was at prime.

The younger monks seemed almost foreign to him, untutored somehow, though by that he did not mean they lacked vocation. And the infant oblates—there were five of them ranging in ages from eight to fourteen, given to the abbey by their parents—he loved them as a father should. He did not stint in his affection. But why did he feel this terrible impatience, this lack of charity toward the young? God may have written that a child would lead, but to Abbot Walter’s certain knowledge none had led him. The ones he truly loved were the men of his own age with whom he had shared so much, from whom he had learned so much. And it was those men who were all so ill and languishing, as if God wanted to punish him by punishing them. Only how could he believe in a God who would do such a thing?

Until yesterday only he and Brother Blaise of the older monks still held on to any measure of health. He discounted the aching in his bones that presaged any winter storms. And then suddenly, before compline, Blaise had collapsed. Hard work and prayer, whatever the conventional wisdom, broke more good men than it healed.

The abbot suddenly remembered a painting he had seen in a French monastery the one time he had visited the Continent. He had not thought of it in years. It represented a dead woman wrapped in her shroud, her head elaborately dressed. Great white worms gnawed at her bowels. The inscription had shocked him at the time: Une fois sur toute femme belle … Once I was beautiful above all women. But by death I became like this. My flesh was very beautiful, fresh and soft. Now it is altogether turned to ashes. … It was not the ashes that had appalled him but the worms, gnawing the private part he had only then come to love. He had not touched a woman since. And that Blaise, the patrician of the abbey, would be gnawed soon by those same worms did not bear thinking about. God was very careless with his few treasures.

With a shudder, Abbot Walter pushed the apostasy from his mind. The Devil had been getting to him more and more of late. Cynicism was Satan’s first line of offense. And then despair. Despair. He sighed.

“Open the door, my son,” Abbot Walter said putting it in his gentlest voice, “my hands are quite full.”

Like the dortoir, the infirmary was a series of cells off a long, dark hall. Because it was January, all the buildings were cold, damp, and from late afternoon on, lit by small flickering lamps. The shadows that danced along the wall when they passed seemed mocking. The dance of death, the abbot thought, should be a solemn stately measure, not this obscene capering Morris along the stones.

They turned into the misericorde. There was a roaring fire in the hearth and lamps on each of the bedside tables. The hard bed, the stool beside it, the stark cross on the wall, each cast shadows. Only the man in the bed seemed shadowless. He was the stillest thing in the room.

Abbot Walter walked over to the bed and sat down heavily on the stool. He stared at Blaise and noticed, with a kind of relief crossed with dread, that the man’s eyes moved restlessly under the lids.

“He is still alive,” whispered the abbot.

“Yes, but not, I fear, for long. That is why I sent for you.” The infirmarer, Brother Geoffrey, moved suddenly into the center of the room like a dancer on quiet, subtle feet. “My presence seems to disturb him, as if he were a messenger who has not yet delivered his charge. Only when I observe from a far corner is he quiet.”

No sooner had Geoffrey spoken than the still body moved and, with a sudden jerk, a clawlike hand reached out for the abbot’s sleeve.

“Walter.” Brother Blaise’s voice was ragged.

“I will get him water,” said the novice, eager to be doing something.

“No, my son. He is merely addressing me by name,” said the abbot. “But I would have you go into the hall now and wait upon us. Or visit with the others. Your company should cheer them, and a man’s final confession and the viaticum is between himself and his priest.” The abbot knew this particular boy was prone to homesickness and nightmares and had more than once wakened the monastery hours after midnight with his cries. Better he was absent at the moment of Blaise’s death.

The novice left at once, closing the door softly. Geoffrey, too, started out.

“Let Geoffrey stay,” Blaise cried out.

Abbot Walter put his hand to Blaise’s forehead. “Hush, my dear friend, and husband your strength.”

But Blaise shook the hand off. “The babe himself said to me that it should be writ down.”

“The babe?” asked the abbot. “The Christ child?”

“He said, ‘Many of those who shall read or shall hear of it will be the better for it, and will be on their guard against sin.’” Blaise stopped, then, as if speaking lent him strength he otherwise did not have, he continued. “I was not sure if it was Satan speaking—or God. But you will know, Walter. You have an instinct for the Devil.”

The abbot made a clicking sound with his tongue, but Blaise did not seem to notice. “Let Geoffrey stay. He is our finest scribe and it must be written down. His is the best hand and the sharpest ear, for all that you keep him laboring here amongst the infirm of mind and bowels.”

The abbot set his mouth into a firm line. He was used to being scolded in private by Blaise. He relied on Blaise’s judgments, for Blaise had been a black canon of great learning and a prelate in a noble house before suddenly, mysteriously, dedicating himself to the life of a monk. But it was mortifying that Blaise should scold in front of Geoffrey who was a literary popinjay with nothing of a monk’s quiet habits of thought. Besides, Geoffrey entertained all manner of heresies, and it was all the abbot could do to keep him from infecting the younger brothers. The assignment to the infirmary was to help him curb such apostatical tendencies. But despite his thoughts, the abbot said nothing. One does not argue with a dying man. Instead he turned and instructed Geoffrey quietly.

“Get you a quill and however much vellum you think you might need from the scriptorium. While you are gone, Brother Blaise and I will start this business of preparing for death.” He regretted the cynical tone instantly though it brought a small chuckle from Blaise.

Geoffrey bowed his head meekly, which was the best answer, and was gone.

“And now,” Abbot Walter said, turning back to the man on the narrow bed. But Blaise was stiller than before and the pallor of his face was the green-white of a corpse. “Oh, my dear Blaise, and have you left me before I could bless you?” The abbot knelt down by the bedside and took the cold hand in his.

At the touch, Brother Blaise opened his eyes once again. “I am not so easily got rid of, Walter.” His lips scarcely moved.

The abbot crossed himself, then sat back on the stool. But he did not loose Blaise’s hand. For a moment the hand seemed to warm in his. Or was it, the abbot thought suddenly, that his own hand was losing its life?

“If you will start, father,” Blaise said formally. Then, as if he had lost the thread of his thought for a moment, he stopped. He began again. “Start. And I shall be ready for confession by the time Brother Geoffrey is back.” He paused and smiled, and so thin had his face become overnight it was as if a skull grinned. “Geoffrey will have a retrimmed quill and full folio with him, enough for an epic, at least. He has talent, Walter.”

“But not for the monastic life,” said the abbot as he kissed the

stole and put it around his neck. “Or even for the priesthood.”

“Perhaps he will surprise you,” said Blaise.

“Nothing Geoffrey does surprises me. Everything he does is informed by wit instead of wisdom, by facility instead of faith.”

“Then perhaps you will surprise him.” Blaise brought his hands together in prayer and, for a moment, looked like one of the stone gisant carved on a tomb cover. “I am ready, father.”

The opening words of the ritual were a comfort to them both, a reminder of all they had shared. The sound of Geoffrey opening the door startled the abbot, but Blaise, without further assurances, began his confession. His voice grew stronger as he talked.

“If this be a sin, I do heartily repent of it. It happened over thirty years ago but not a day goes by that I do not think on it and wonder if what I did then was right or wrong.

“I was confessor to the King of Dayfed and his family, a living given to me as I was a child of that same king, though born on the wrong side of the blanket, my mother being a lesser woman of the queen’s.

“I was contented at the king’s court for he was kind to all of his bastards, and we were legion. Of his own legal children, he had but two, a whining whey-faced son who even now sits on the throne no better man than he was a child, and a daughter of surpassing grace.”

Blaise began to cough a bit and the abbot slipped a hand under his back to raise him to a more comfortable position. The sick man noticed Geoffrey at the desk in the far corner. “Are you writing all of this down?”

“Yes, brother.”

“Read it to me. The last part of it.”

“… and a daughter of surprising grace.”

“Surpassing. But never mind, it was surprising, too, given that her mother was such a shrew. No wonder the king, my father, turned to other women. But write it as you will, Geoffrey. The words can change as long as alteration does not alter the sense of it.”

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

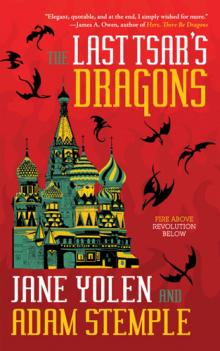

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

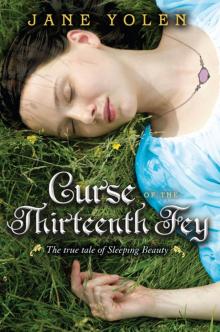

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

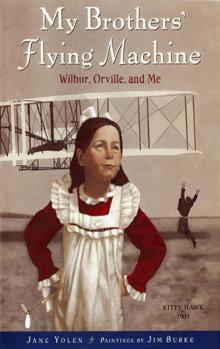

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

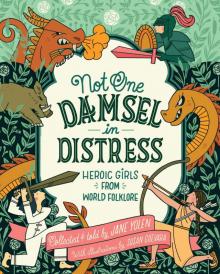

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

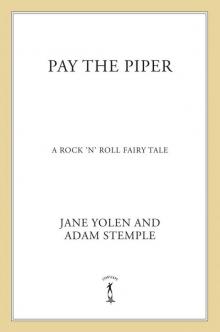

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

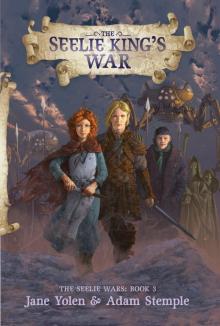

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

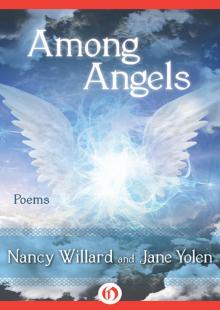

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

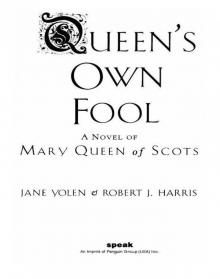

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool