- Home

- Jane Yolen

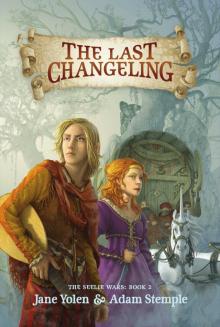

The Last Changeling Page 3

The Last Changeling Read online

Page 3

“Insist away, popinjay,” she said. Aspen towered over her, but he couldn’t help noticing how broad her shoulders were and how thick her fists. Her ears, too, were swollen and misshapen, as if she’d spent a lifetime in and out of wrestling holds.

Lovely, Aspen thought. I am about to be beaten bloody by a creature I could step over.

“Now, let us reconsider,” he said quickly, then remembering a minstrel shouldn’t sound like a prince, changed it to “I mean, let’s hold on a moment.”

If anything, the female’s grin grew wider and she took a step toward him. “Why?”

“Because . . .” Aspen began, but stopped and thought, Yes, because why? They owe you no allegiance. No one does. Because of you, thousands of innocent Seelie folk will probably be slaughtered. And thousands of Unseelie, too. Though that wouldn’t be such a disaster. Except for the innocents, like the midwives. And the potboys. And my tutor, Jaunty. And . . . He bit his lower lip, thinking, You are reviled in both lands, and rightfully so. The only person in all the realms who likes you even a little is . . .

“Snail,” he said.

“Because . . . Snail?” the female mocked him, then guffawed heartily. “The air thin up there, elfling?”

Aspen shook his head, half in answer and half to clear it. “No, I . . . it’s just . . .”

“Yes?”

He took a deep breath and gathered himself. Obviously no manners or courtesy will work here. He took another peek at the female dwarf’s cabbage ears. His right hand pawed reflexively at the spot on his belt where his sword would normally hang. And violence is right out, too. Sighing, he straightened his back and tugged the hem of his jacket straight. If I am to be bludgeoned to death, I will carry it off as nobly as possible. “It is just that the only friend left to me in all the world is now inside that wagon.”

The female’s grin waned as he continued.

“And you can mock me, or beat me, or even kill me.” He put a brave foot forward. Well, not an actual foot, more like a toe. “But you cannot keep me from her.”

The dwarf’s grin left her face entirely, but she didn’t move out of the way. Aspen took a full step forward and steeled himself to walk over or through or around her.

Brave words, he thought, but putting them to action is going to be another thing altogether.

He gulped and had just lifted the toes of his right foot off the ground when one of the male dwarfs spoke.

“Skrek!”

Aspen thought that meant “Listen up!” Or “Halt!”

“Brave words,” the dwarf said, as if reading Aspen’s mind, “and bravely spoken.” He turned to the female. “The professor would like those words.”

The other male chimed in. “Put them in one of his plays, he would.”

“He’s a fine one with the words is the professor,” said the first.

“Not like our sister, Dagmarra,” said the second.

“She’s a fine one with her fists.”

“And her forehead.”

“And her knees.”

“And elbows.”

“And feet, and fingers.”

“And her ax. Dinna forget the ax.”

“The ax.”

The flurry of words from the male dwarfs buffeted Aspen’s ears and he took an involuntary step backward.

Dagmarra smiled at his stumbling, showing off all six of her teeth. “’Tis true,” she said, “I’m a fine one with all that.”

“Now, tell her she would’ve beaten you,” the first dwarf said.

Aspen nodded immediately. “Bloody,” he said, knowing it was true.

“You had nah chance at all,” the second dwarf said.

“None whatsoever.”

The two brothers looked to their sister, who shrugged. And stepped aside.

“I am Annar,” the first dwarf said.

“And I am Thridi,” said the second.

“And you are accepted into our hule.”

The last bit sounded like a formal welcome, though whether he had just been accepted into their house, their kinship group, or their dinner table, Aspen was not certain, but he bowed respectfully nonetheless. “I thank you, good sirs.” He turned and made another bow toward the female.

“May I ask you a question?” he began, thinking to bring up the Sticksman and perhaps find an answer to the questions he’d been geased. But before he could address her or step up and open the door to the cart, he heard hoofbeats. Lots of them.

He looked back down the road and saw a troop of mounted soldiers dressed in the livery of his father, the king. It was surely the troop that had gone by before.

Bother! he thought. But at least Snail is safe.

“Hold,” Annar and Thridi said at the same time.

Aspen gulped. “Why do . . . don’t I go on in while you . . . um . . . talk to the soldiers.” The horses with their fierce-looking riders were already closer than he would have liked. Almost close enough to see me, he thought. And if my brother is leading them, I will be taken. His jaw was stiff. He knew he looked grim. Or frightened. Or both.

But at least they will not get Snail. He shuffled his feet impatiently. Still, it would be better if neither of us is found out.

“You’re nah going in without me,” Dagmarra said.

“And she’ll nah be with you without us,” Annar added.

“But . . . Nomi . . .” He found himself stumbling over Snail’s false name. Said it again with a bit more authority. “Nomi went in without you.” He tried not to whine, but at this point the soldiers were so close, and he could not quite keep the panic out of his voice.

“She is skarm drema,” the three dwarfs said as one, as if that explained anything.

But of course, it didn’t.

And now Dagmarra blocked the door and the soldiers blocked the road and Aspen was left with nothing but a lute to defend himself with. A lute with a carved and battered angel on the top of its neck, perhaps foreshadowing how Aspen would look once the soldiers caught hold of him.

Maybe, he thought, I could hang myself quickly with the strings and save them all the trouble.

SNAIL’S ODD ENCOUNTER

The next room was fully lit. Instead of the starkness of the caped creature’s room, or the snugness of the dwarfs’ room, this one looked like a place in the Unseelie palace, luxurious enough for a queen to give birth in or see ambassadors.

Snail spun around slowly, taking it in. Was this then the professor’s room? All she knew of professors were that they taught dry old facts like how many Hobs could dance in a pentagram or what moon was most propitious for birth-giving or burial, or the list of the kings of the Unseelie Realm down to the fiftieth generation. Though, since her only teachers had been midwives, and professors never seemed to have babies (though how they multiplied she’d never been able to figure out), she’d never actually met one before. A professor might be as tall and thin as the Sticksman or as broad and brangling as a Border Lord. It was silly to speculate. But the room itself might hold some clues.

The one bed was enormous, with pillows of all sizes and shapes piled high and covered with cloth of silver and gold. No one in the Unseelie world was allowed cloth of silver except a prince or princess; none allowed cloth of gold except the king or queen.

Snail drew in a quick breath. Perhaps . . . she thought . . . perhaps the professor is married and needs a midwife. Perhaps that’s what skarm drema meant and why I’ve been brought inside. It was an interesting idea, and she considered it for a moment.

Drawing herself up, she recited the midwife creed silently, and prepared to get down to work: Anticipate, alleviate, and then await. She’d need hot water and soap. Wondered how that might work, given this was a wagon and they were some ways to the last stream.

She snapped her finger. Prince Aspen could say the fire charm and . . .

/>

Stupid, she muttered, if he did such a daft thing, he’d be giving himself away.

She was puzzling this over when another door suddenly creaked open, this one by the right side of the bedstead. It was an ominous sound. She stood ready to flee back into the room with that annoying bird.

However, instead of something fierce coming through the door—like an ogre or troll—in glided the most beautiful woman Snail had ever seen. She was more beautiful than the twin princesses Sun and Moon, who wore their boredom on their faces, more beautiful than the Unseelie queen, who had every kind of glamour at her fingertips.

This was no professor’s wife, who would undoubtedly have been a dowdy and difficult patient wanting to know all the midwifery secrets before giving birth. The woman was clearly one of the ancient Seelie goddesses. No one else could be that beautiful and serene.

Snail managed a quick and adequate curtsey, though her right knee creaked and the left one locked.

The beautiful woman glided soundlessly right up to her and held out her hand. “I am Maggie Light,” she said, in a voice that was sweet without being cloying, strong without being demanding. “Not Dark. Not dark at all. Remember that.”

“I will, goddess,” Snail whispered to the hand.

There was a tinkling sound that Snail just managed to realize was a laugh, not bells. The proffered hand did not move away, just dangled there, as if waiting, just at Snail’s sight line. At last, she realized that this Maggie Light wanted to help her up out of the curtsey.

Tentatively, Snail reached for the hand and was dragged up to her feet, like a fish caught on a hook and line.

“There, that is better,” said Maggie Light.

“Better than what?” Snail muttered. But she knew. It was better than being in a dungeon or at the end of a rope. Better than being captured by one or two armies. Better than being devoured by a carnivorous merman . . .

“Now I can see your pretty face.”

Pretty? Snail couldn’t tell if Maggie Light always overcomplimented her visitors or if she was making a joke. Or, perhaps, she was blind. Snail dared a glance at her.

Maggie Light’s eyes were a strange color, a kind of silver.

And who has silver eyes, Snail thought, except—maybe—a fish? She tried to think of Maggie Light as a fish. A mer. She shuddered, wondering how sharp the woman’s teeth were.

Almost as if reading Snail’s mind, Maggie Light smiled. Her teeth were small, white, and even as pearls on a necklace. There was no threat in them. “Why have you come here, child?”

All Snail could think of to say in answer was what the dwarfs had said, the words that had worked before: “Skarm drema!”

“Ah,” Maggie Light said, turning away from Snail and gliding over to a nearby desk. The desk had a slanted top and there was an open book lying there with ruled lines going both sideways and up and down.

Snail followed her and looked at the book. Things were scribbled on the page in blue and red inks.

“You are not in the diary,” Maggie Light said, pointing a perfect finger at the book. “He has not put you in the diary. How unusual.”

Snail shrugged. “Maybe he didn’t know I was coming.”

“But if you are truly skarm drema, he will know you are here.”

“I didn’t know I was here. Or even know I was coming here. Until I was here, that is,” Snail said. Now that she knew she wasn’t needed for a birth and she wasn’t about to be eaten by an ogre or merman or troll, her irritation was beginning to show.

“Nevertheless,” said Maggie Light, and then she was suddenly no longer paying attention to Snail. Instead, head cocked to one side like a bird, she stood still as stone, listening to something else. Something that Snail couldn’t hear.

At last Maggie Light moved and, turning her head, announced, “He comes.”

“Who? The professor?” asked Snail, adding, “And by the way, what does he profess?”

“That he will tell you himself,” said Maggie Light, gliding soundlessly toward the bed as if stepping out of the way.

Out of the way of what? Snail wondered. But before she could even try to guess, the bookcase by her side swung wide and she had to scramble to avoid being hit. It was a third door into the room. Is three the charm?

A figure strode through.

Snail had been expecting someone taller. Someone fiercer. Someone . . . consequential.

The man who came through the door was small and round, a gourd of a man, with thinning hair, a short grey goatee, and twinkly grey eyes. Grey. No one in the Seelie Courts had grey eyes. Unless . . . unless perhaps they were related to fish. She wondered if it was a coincidence that both the professor and Maggie Light had grey eyes. Father and daughter? Uncle and niece? Some other family connection she wasn’t acquainted with?

“Hello,” the man said in a voice like bubbling water. “Nice to have you here, here being the operative word. At least the way we operate.”

“Operate? Are you a doctor then?” Snail asked.

“I can strike a set but not set a leg,” he told her. “I can boil a lance but not lance a boil. I . . .”

Decidedly not a fish, Snail thought. Fish folk rarely spoke above water, or so she’d heard. The one mer she’d had a close encounter with had said nothing.

“. . . I’m Professor Odds,” he said, before adding, “Odds are you weren’t expecting someone like me.”

In a day of strangeness, he was perhaps the oddest thing of all.

ASPEN’S LOUTISH CAST

Aspen pulled off his lute and fervently wished for his lost hat to hide his face. As he did so, he remembered his speech to Snail about the “hooded face” and the “concealing cloak.”

Brave words, he thought, but putting them to practice is proving harder than I thought. He peered at the oncoming horsemen, trying to see if he recognized any of them. Or if any of them seemed to recognize him. He thought of swinging his lute like a weapon to hold off the soldiers, but quickly realized how useless that would be.

The incoming riders were only a small company, but a company nonetheless and plenty big enough to capture a single princeling and a midwife’s apprentice.

Maybe if I surrender quietly, they won’t look for Snail. For some reason this was the thought that calmed him. He nodded to himself. If I cannot win, at least I can lose with dignity.

He caught Annar looking at him and then at the approaching soldiers. Then the dwarf exchanged a quick glance with his brother. Aspen thought something wordless passed between them. He had no idea what and had no time to ask. The soldiers were nearly upon them.

“Tune it,” Thridi said to Aspen, pointing at the lute.

Aspen was surprised but did as Thridi asked, as the two brothers stepped out in front of the first pair of trotting horses.

“Hello and be welcome!” Annar hailed them.

“Be welcome and hello!” Thridi called.

Aspen stared over the dwarfs’ heads at the officers at the front of the column. He didn’t recognize either of them. But surely they have a description of me. One good look and . . .

He heard a loud, sharp whistle and then the sound of a door slamming. As he started to turn toward the sound, a low hiss interrupted his thoughts.

“Tune it louder, foolish popinjay, and dinna look backward, never backward,” Dagmarra whispered, stepping in front of him.

He saw something white stuffed into her ears but had little time to wonder at it.

“Welcome, hello, and be!” Dagmarra shouted while each of the three siblings dropped into a low bow.

Which from a dwarf, Aspen thought wildly, is very low indeed.

“Tune!” Dagmarra said again, hissing as if in a whisper, though it was hardly that. More of a hushed shout, as if she had no idea how loud her voice was. “And dinna make it soft.”

Aspen continue

d to tune his lute, all the while keeping an eye on the coming soldiers.

The officer in charge, a captain by the stripes on his left shoulder, kicked his horse forward a step. His long ears marked him as old for his job, though his face was relatively unlined. Judging by the frayed coat he wore, the single battle medal on his chest, and the small number of soldiers he commanded, Aspen thought the captain was probably not from a good family or otherwise well connected.

The captain looked down his long nose at the strange tableau before him and wrinkled his brow. “Well met, Little Folk,” he said, nodding his head at the bowing dwarfs. Then he turned his gaze to Aspen. “And . . . minstrel?”

The captain’s eyes bored into his, and Aspen was sure he was about to be called out. Though he didn’t recognize the officer, by the way the captain was staring, he surely suspected something.

He knows it is me, Aspen thought. He is only playing games now, waiting for me to confess. Aspen set his feet in a wider stance to keep from trembling, and straightened his shoulders. Well, I shall not confess. If I am to be captured, it will not be by my own admission. And I will give this petty tyrant—this underthing, this nobody—no enjoyment of the . . .

Suddenly, Aspen was bent over at the waist and struggling for a breath. Dagmarra’s face was level with his own and he smelled the rotten-gums stench of her breath. It took a moment for him to realize she had just turned and punched him in the stomach. Hard! How she missed destroying the lute with the blow he could not figure out.

“Bow down to your betters, you scurvy music maker,” she said, rather loudly into his face, her perilous breath wafting even farther into his own mouth. Loud enough, he was sure, for the whole troop to hear and laugh at him.

But better, he thought, to be laughed at that than dangle at the end of a rope. Though—and of this he was certain—certainly not as noble.

“Yes,” Annar said pleasantly to the captain, “that is our minstrel.”

“A talented musician,” Thridi added. “Though a bit touched in the head.”

“Thick as soup,” said Annar. “If truth be told.”

The Pictish Child

The Pictish Child Cards of Grief

Cards of Grief A Plague of Unicorns

A Plague of Unicorns Heart's Blood

Heart's Blood Mapping the Bones

Mapping the Bones Snow in Summer

Snow in Summer Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard

Merlin's Booke: Stories of the Great Wizard Centaur Rising

Centaur Rising The One-Armed Queen

The One-Armed Queen Dragon's Blood

Dragon's Blood Boots and the Seven Leaguers

Boots and the Seven Leaguers The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales

The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales The Wizard of Washington Square

The Wizard of Washington Square Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder The Emerald Circus

The Emerald Circus Sister Light, Sister Dark

Sister Light, Sister Dark Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast

Twelve Impossible Things Before Breakfast The Devil's Arithmetic

The Devil's Arithmetic Trash Mountain

Trash Mountain The Dragon's Boy

The Dragon's Boy A Sending of Dragons

A Sending of Dragons The Young Merlin Trilogy

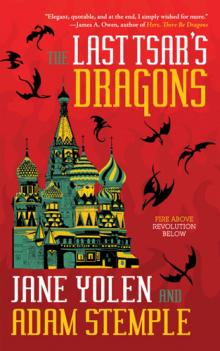

The Young Merlin Trilogy The Last Tsar's Dragons

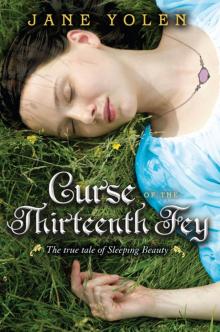

The Last Tsar's Dragons Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey: The True Tale of Sleeping Beauty The Bagpiper's Ghost

The Bagpiper's Ghost Nebula Awards Showcase 2018

Nebula Awards Showcase 2018 Hobby

Hobby How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale: 2 Children of a Different Sky

Children of a Different Sky Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy

Commander Toad and the Intergalactic Spy Wizard’s Hall

Wizard’s Hall The Transfigured Hart

The Transfigured Hart Dragonfield: And Other Stories

Dragonfield: And Other Stories The Magic Three of Solatia

The Magic Three of Solatia The Great Alta Saga Omnibus

The Great Alta Saga Omnibus Favorite Folktales From Around the World

Favorite Folktales From Around the World Passager

Passager The Wizard's Map

The Wizard's Map The Last Changeling

The Last Changeling Except the Queen

Except the Queen Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All

Snow in Summer: Fairest of Them All: Fairest of Them All The Midnight Circus

The Midnight Circus Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast

Atalanta and the Arcadian Beast Finding Baba Yaga

Finding Baba Yaga The Rogues

The Rogues Dragon's Boy

Dragon's Boy The Hostage Prince

The Hostage Prince Wizard of Washington Square

Wizard of Washington Square How to Fracture a Fairy Tale

How to Fracture a Fairy Tale Magic Three of Solatia

Magic Three of Solatia Curse of the Thirteenth Fey

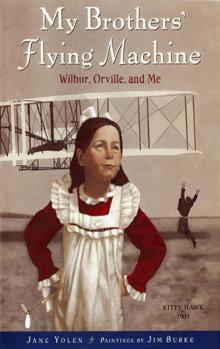

Curse of the Thirteenth Fey My Brothers' Flying Machine

My Brothers' Flying Machine Not One Damsel in Distress

Not One Damsel in Distress Merlin's Booke

Merlin's Booke Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale

Pay the Piper: A Rock 'n' Roll Fairy Tale Merlin

Merlin Troll Bridge

Troll Bridge Pay the Piper

Pay the Piper Dragonfield

Dragonfield Sister Emily's Lightship

Sister Emily's Lightship Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons

Hippolyta and the Curse of the Amazons Prince Across the Water

Prince Across the Water Dragon's Heart

Dragon's Heart The Seelie King's War

The Seelie King's War Among Angels

Among Angels Queen's Own Fool

Queen's Own Fool